Chapter 21: ROTC Advanced Camp — Summer of 1980

- Anthony Carbone

- Aug 22, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Sep 20, 2025

BELIEVE NOTHING YOU HEAR, AND ONLY HALF OF WHAT YOU SEE — A Memoir of Service, Shame, and the Search for Truth

Time for Army ROTC Advanced Camp

After finishing my junior year at Notre Dame — three years of increasingly difficult Military Science courses, drill, and early morning PT — it was finally time for the crucible of every Army ROTC cadet: Advanced Camp. This was the moment where all of the classroom lessons, field exercises, and countless hours in uniform were put to the test.

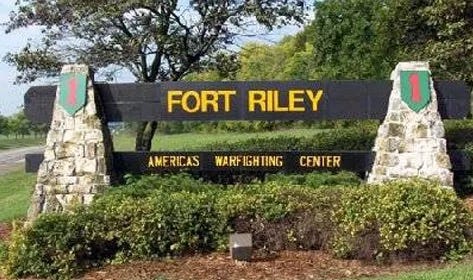

Report to Camp Forsyth

I reported to Camp Forsyth at Fort Riley, Kansas, in June of 1980 and would spend the next six weeks there. Notre Dame cadets trained side by side with the Aggies of Texas A&M and cadets from Army ROTC programs across the country. Today, Advanced Camp is held at Fort Knox, Kentucky, but in 1980, Fort Riley was the proving ground. The open Kansas plains — scorched by the summer sun, whipped by winds, and alive with biting insects — were where we would be pushed to our limits and measured against the Army’s highest standards.

The Heat Wave

The summer of 1980 was brutal. A historic heat wave and drought gripped Kansas, and we felt every bit of it in our old steel pot helmets and full combat gear as we marched and trained. Day after day, the thermometer climbed past 100 degrees, with July delivering more than two weeks of triple-digit heat. The ground was dry and cracked, the air stifling, and shade was almost nonexistent. The oppressive heat wasn’t just uncomfortable — it was dangerous. For us cadets, it meant pushing our bodies to the brink of exhaustion and dehydration, learning to function in conditions that were as much a test of survival as they were of soldiering.

Cut Off From Home

Another reality of Advanced Camp in 1980 was how completely cut off we were from the outside world. This was a dozen years before personal cell phones existed. Letters were allowed, but only when we had a sliver of free time — and there wasn’t much of that. On weekends, we were marched to an area that had a dozen or so payphones lined up, each with a line of cadets waiting their turn. I would stand in the blazing sun, sometimes for over an hour, just for the chance to place a call.

Every time I finally reached Mariann, my heart would race. The connection was scratchy, the time was short, but it didn’t matter. I would speak a mile a minute, trying to cram in everything I had just survived — the marches, the heat, the evaluations — and, most of all, to tell her how much I missed her. Those brief conversations sustained me. They were my lifeline.

Life in the Barracks

We were housed in old wooden World War II–era barracks — no frills and stripped bare of comfort. There was no air-conditioning, just two long rows of metal bunk beds. Each of us got a thin mattress, two white sheets, a goose feather pillow, and one rough-as-hell olive drab wool blanket that itched like crazy. A battered footlocker sat at the end of the bunk, with a metal locker nearby for uniforms and gear. Privacy didn’t exist. The showers were one big room with a dozen shower heads, and the toilets were lined up side by side — twelve seats in a row, no stalls, no doors. I used to sign up for Fire Guard duty around 2200 so that I could sneak to the latrine when most guys were asleep. That was the only way to find a little peace and privacy.

Mornings were brutal. At the crack of dawn, the drill sergeant would storm in, flick on the lights, and bang something metal against the bunks as he marched down the aisle. We’d jolt awake, scrambling out of bed in our white boxers and t-shirts, and line up at the foot of our racks for headcount and instructions. Then it was a mad rush to throw on PT gear and fall into formation outside.

Physical Training and Jodies

PT always ended the same way — running in step while the drill sergeant belted out Jodies. They were crude, funny, and loud, keeping us in cadence while building that strange mix of misery and camaraderie. For example, everyone has heard, “C-130 rolling down the strip. 64 Airborne on a one-way trip. Stand up, hook up, shuffle to the door. Jump right out and count to four.”

Back at the barracks, just when you thought PT was over, there’d be more push-ups: “Front Leaning Rest Position! Move! One, two, three, four!” Over and over until our arms shook. Then five minutes — literally five minutes — to shower, shave, brush teeth, and dress into fatigues and boots. By the time we formed up outside and marched to the mess hall, the day had barely begun.

The Mess Hall

Getting chow felt like stepping into one of those old war movies. A long line of cadets in fatigues and combat boots stood at Parade Rest, hands clasped behind their backs. The chow hall itself was just another converted WWII barracks — bare, loud, and echoing with the clatter of trays. But with the aroma of chow.

Behind a wall of glass ran the chow line, steam curling up from metal pans. You grabbed a tray and tin dinnerware, then shuffled sideways as cadets on KP duty slapped food onto plates — scrambled eggs, greasy bacon, and a biscuit drowned in SOS (“Shit on a Shingle”). At the end, you snatched a cup of milk or juice, then dropped into a seat with your squad. You had maybe six minutes — no more — to eat, scrape your plate, and move. Not much time for chit-chat.

C-Rations

When we weren’t eating in the mess hall, the alternative was C-Rations in the field. Even on an empty stomach, most of those little brown boxes were tough to swallow. I quickly learned to sprint to the mess truck when it pulled up, fighting my way to the best meals before they were gone. My prize was B-1Unit— a small can of tuna fish paired with a large can of fruit cocktail. Compared to the other canned meats, it felt like gourmet dining. My second choice was beans and franks, but only in a pinch. Since we rarely had the chance to heat our meals, the tuna and fruit were the safest bet. Everything else I was quick to trade, always hoping to score a pack of Chicklet gum, which was like gold in the field.

Learning to Be a Soldier

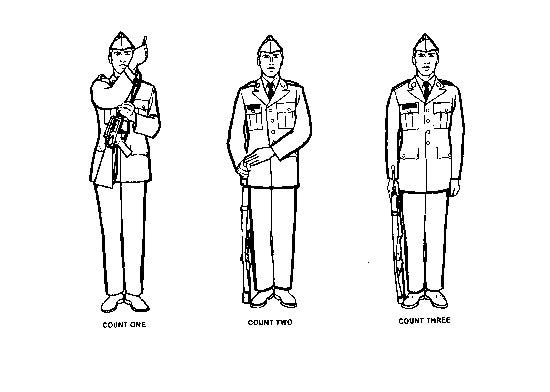

A large part of Advanced Camp was learning to be a soldier first, and an officer second. We learned to wear our uniforms and gear correctly, to stand in formation, and execute all the basic commands: Fall In, Attention, Parade Rest, Present Arms, At Ease, Fall Out. We drilled endlessly on marching and running in formation, our cadence echoing across the field.

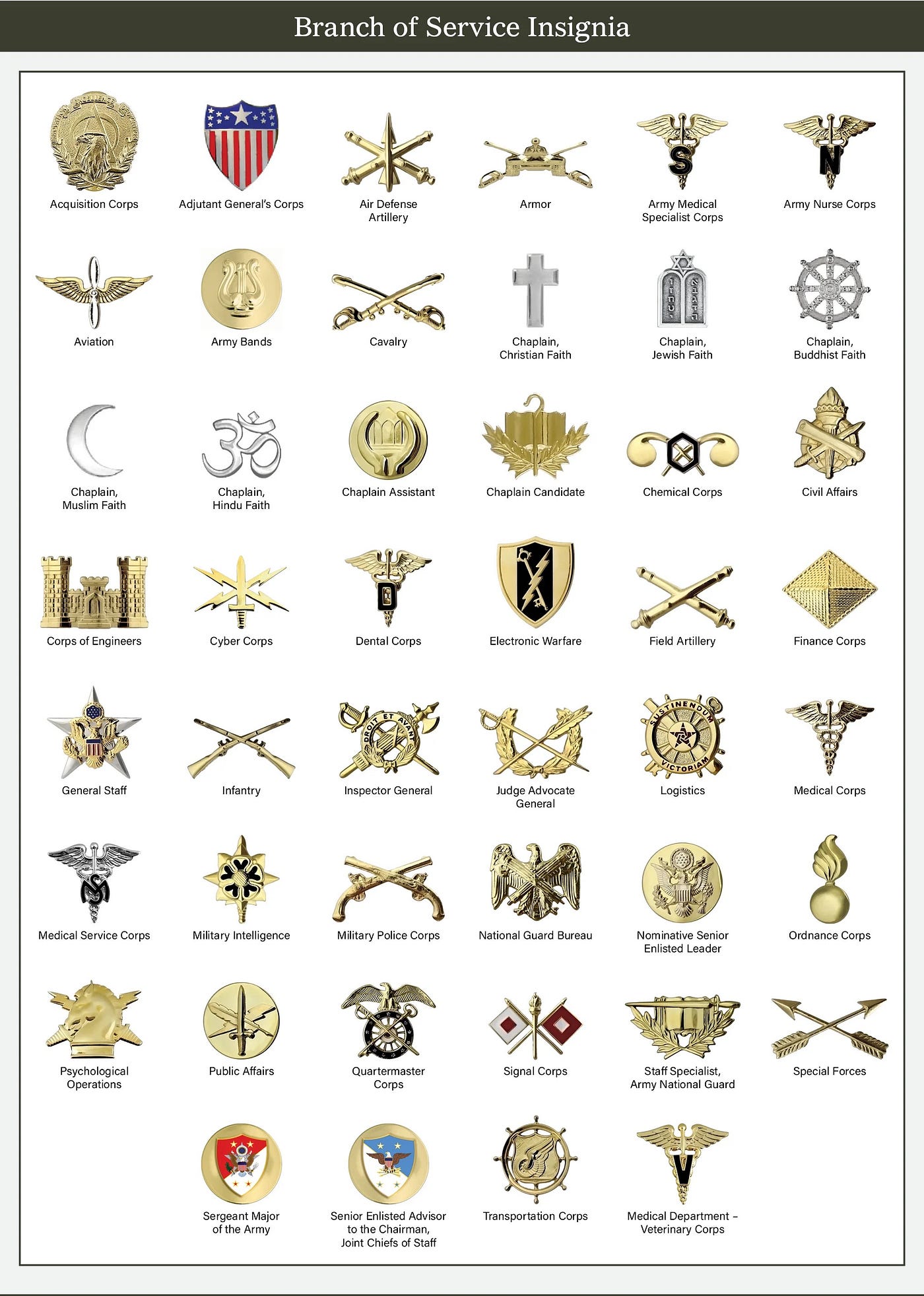

We had to learn the rank and branch insignia (something you already learned in basic ROTC).

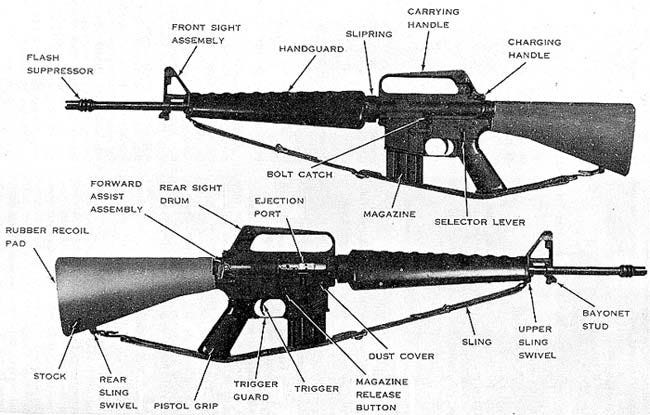

The M16 Rifle

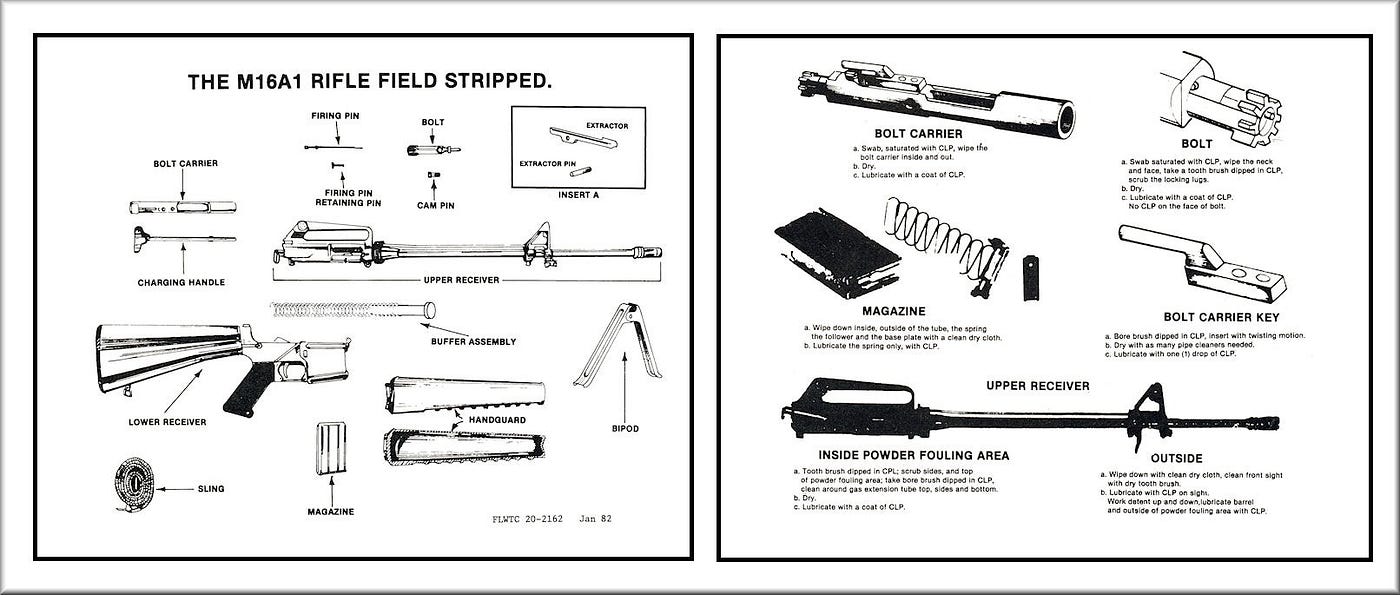

Then came the rifles. Each of us was issued an M16A1 rifle. We learned to carry it, field strip it, and reassemble it faster and faster.

We practiced the 15-Count Manual of Arms. Right shoulder, Arms. Port, Arms. Left shoulder, Arms. Present, Arms. Order, Arms. Then something to the effect of singing, “This is my rifle, this is my gun. This is for fighting, this is for fun.”

Eventually, we moved to the firing range. The rules there were strict — no motion without a direct order. We learned to load, fire, and zero our weapons. Shooting from standing, kneeling, and prone positions, clearing jams, and obeying every command was terrifying — and exhilarating. After each round, the Range Officer called, “Are there any alibis?”Those with rounds left had to empty their magazines immediately.

Afterward, we marched back to the garrison, rifles in arms, singing Jodies, only to face the dreaded cleaning of weapons. Practiced field stripping our M16A1. Tedious, meticulous work, but essential. An M16 that wasn’t spotless could fail when it mattered most.

The Water Hazards

Army ROTC Advanced Camp seemed obsessed with water obstacles. No matter where we turned, there was always some new challenge over a lake, pond, or river. The cadre loved to test our courage and balance above the water, knowing full well that most cadets dreaded falling in.

One of the first obstacles I faced was a balance beam stretched high over a lake. The beam wobbled with every step, and the thought of tumbling into the water below made it feel like a tightrope walk in the circus. Somehow, I managed to keep my footing and make it across.

Rope Over Water

Another test was even more intimidating. I had to climb a wooden stand high above the lake, shimmy out onto a thick rope, and crawl to its midpoint, where a “Recondo” sign dangled. Once I touched it, the special forces sergeant on shore barked through a bullhorn, “Hang from the rope, cadet, and request permission to drop!” I dangled from the rope and shouted, “Cadet Carbone, request permission to drop!” The sergeant’s reply stunned me: “Carbone? Like Major Tony Carbone of MACV-SOG? Carbone?” I yelled back, “Yes, Sergeant!” He paused, then shouted, “I know your father. Give me ten pull-ups before you drop, Cadet!” So I did my pull-ups, arms burning, before finally letting go and plunging twenty meters into the water.

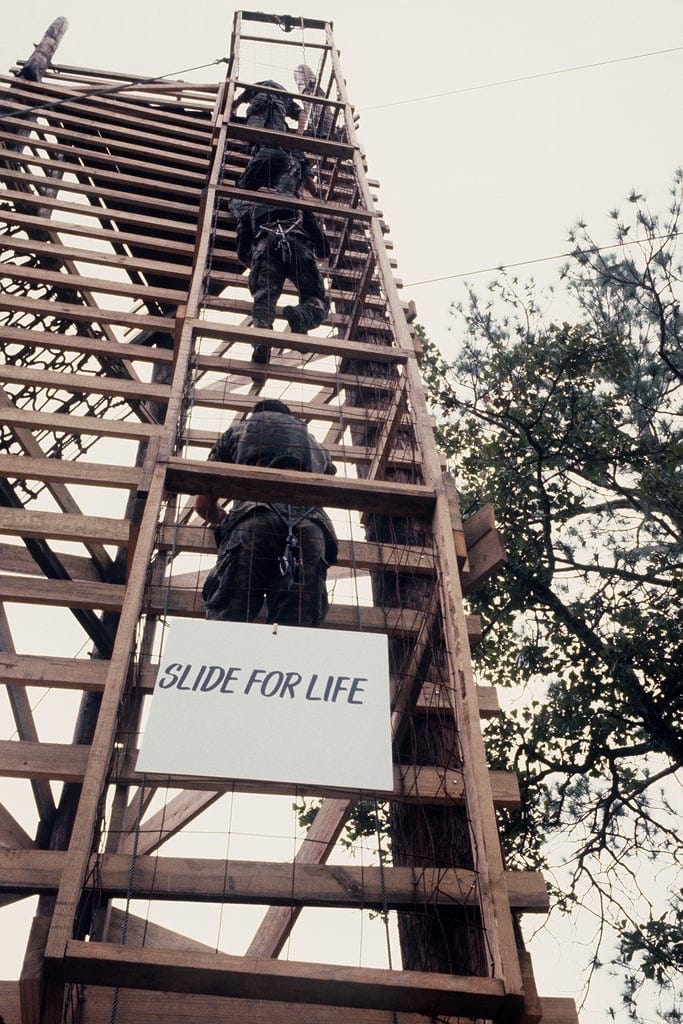

Slide For Life

But the most famous challenge was the Slide for Life (zip line). First, we climbed what felt like a hundred meters up a tower. At the top, a special forces instructor handed me the handle to the zipline trolley. I sat down, ready to launch, but as I started to slip off too soon, he snatched me back by the shoulder and growled, “Not so fast, Cadet!” On my second try, I slid off the tower, hanging low under the rope, racing down toward the beach far below.

On shore, one sergeant shouted instructions through a bullhorn, while another waited with an orange flag. A crowd of cadets cheered from the beach. As I approached, the sergeant yelled, “Lift your legs into an L!” I did as told, gripping the handle until the flag was raised. At that moment, I let go, tumbled into the air, and smacked the lake with so much force that I skipped across the surface, cartwheeled five times before finally sinking in. When I surfaced, sputtering but exhilarated, the other cadets broke into applause.

Weekend Guard Duty and Super Numero

Twice during camp, our platoon had weekend duty. No passes. No fun. Just preparation, inspection, and standing post. The first step was polishing boots. I had an advantage — years of polishing my father’s combat boots gave me a skill my platoon mates lacked.

Next came memorizing the General Orders and learning the Special Orders for that weekend.

Then, the drill sergeant lined us up: “Fall In! Dress Right, Dress! Attention!” One by one, he inspected haircuts, shaves, boots, and uniforms, asking each of us to recite the General Orders. After reviewing the platoon, he announced the Special Orders and designated one cadet as Super Numero, relieved from guard duties for the weekend. I was chosen both times — a tremendous honor, though it didn’t make me popular with my platoon.

Being Super Numero meant I was on my own. I used the time to call Mariann and my family. Standing there, I reflected on all the boots I had polished for my father and the lessons he had taught me. Everything he had instilled over the years had prepared me for this moment, and for the challenges ahead as a cadet — and eventually, an Army officer.

Leadership in the Field

Once we had mastered the basics of soldiering, the remainder of Advanced Camp focused on leadership development. Instructors began selecting a single cadet to serve as the leader for each task or exercise.

We were often broken into 12-man squads, and a squad leader would be chosen to plan and execute the mission. The instructors would give us a Warning Order (WARNO)— a preliminary notice of a mission — then we had to develop a detailed Operation Order (OPORD), outlining objectives, tasks, and support for execution.

When it was my turn, the instructor pointed to an enemy position beyond a large hill. I had two options: the easy route around the hill, or a straight-up assault through a forest of thorn bushes. I chose the hard path.

It was brutal. Thorns tore at our uniforms and skin with every step. The risk paid off — we completely surprised the enemy squad and successfully ambushed them. The instructors were impressed. I received an on-the-spot Special Recognition, one of only a handful awarded among the 5,000 cadets at camp that summer. Once again, my father’s lessons rang true: sometimes the hard route is the right route.

The Leader’s Reaction Course

The next phase of Leadership Development was a full day at the Leader’s Reaction Course (LRC). Rumor had it the course had been developed by former German Field Marshal Rommel, though the origin didn’t matter once you were standing at the edge of a water obstacle with a squad waiting on you.

The course was designed to test everything a future officer needed: decision-making under pressure, clear communication, teamwork, initiative, and the ability to adapt on the fly. Obstacles were both physical and mental, forcing a cadet to think critically while leading a squad of varying strengths, weaknesses, and even injuries.

At Fort Riley, the LRC was a long series of water obstacles. Each challenge required that no one touch the water. A typical scenario involved a shallow pool of dark green water with a tall wall in the center, and we were given a bucket, a roll of rope, and a single wooden board. Fifteen minutes to get the entire squad across. Success required creativity, coordination, and making sure the slowest or weakest cadet crossed safely.

When I was chosen leader, I orchestrated each step, moving all twelve of us across successfully. For this, I earned my second on-the-spot Special Recognition. It was a defining moment, proving that leadership is as much about guiding your team as it is about completing the task.

Recondo

One of the proudest moments of my ROTC Advanced Camp at Fort Riley in 1980 was earning the prestigious Recondo badge. “Recondo” stood for reconnaissance and commando, and only a small percentage of cadets achieved it.

To qualify, we had to exceed the already demanding standards in every graded event. That meant scoring well above average on the Army Physical Fitness Test, negotiating most of the obstacles on the Confidence Course, qualifying sharpshooter or higher on the rifle range, and excelling in land navigation both day and night. We had to complete a six-mile road march in under ninety minutes, pass the grenade assault course, and perform to standard on warrior skills and tactical evaluations.

There was no room for failure — every requirement had to be met on the first try, with no disciplinary blemishes along the way.

Earning Recondo was about more than just physical ability. It demanded focus, consistency, and leadership under stress. By the time I pinned the badge on my uniform, I felt a deep sense of accomplishment. It wasn’t just another award — it marked me as someone who could be counted on to meet the toughest challenges head-on. To this day, I still remember how proud I was to walk away from Advanced Camp with that Recondo badge on my chest and the black and gold tab on my shoulder.

Branch Week

The final phase of Advanced Camp was my favorite — Branch Selection. This was the week when we got a taste of every major branch of the Army before returning to campus for our final year of college and ROTC. Soon, we would have to submit our top three choices for the branch we wanted to serve in after commissioning — a huge decision for any cadet.

The cadre did their best to give us a realistic glimpse of each branch’s life, challenges, and responsibilities.

Infantry

“Queen of Battle”. The foundation of all soldiering. Everything we did at Advanced Camp was Infantry. Marching, maneuvering, firing weapons, and leading squads reinforced everything we had learned.

Artillery

“King of Battle”. We learned to compute target acquisition and fire real Howitzer rounds. We put the fuses on the round. Filled the shell with explosives. Computed the elevation and deflection. And got to pull the lanyard. The recoil and thunder of a shell leaving the tube was unforgettable.

Armor & Cavalry

Combat Arms of Decision”. Tanks, tracked vehicles, and the chance to fire an M60 tank round. A female cadet was chosen for the live-fire demonstration, which was unusual given the 1980s regulations. I knew tanks intimately from my father, and driving around fifty-two tons of steel was exhilarating. Watching them fire rounds downrange was even more thrilling.

Air Defense Artillery

“First to Fire”. Air-conditioned vans filled with radar screens were almost tempting after the heat wave we’d endured for weeks. But something told me that these guys were high-priority targets for the enemy.

Medical Service Corps

To Conserve Fighting Strength”. Ambulances and field hospitals fascinated me, and I knew this branch would tie directly into my future in the Medical Corps.

Aviation

“Above the Rest”. Army airplanes and helicopters were awe-inspiring. Everyone wanted to fly. I struggled between Aviation and Medicine until I realized I could become a Flight Surgeon — combining both passions.

Military Intelligence

Always Out Front”. Their display of Soviet uniforms, AK-47s, maps, and Russian signage captivated me. I tried to decide between Medicine, Aviation, and Intelligence. In the end, practical limitations helped: I couldn’t apply for Aviation because I wore glasses.

Branch Choices

My final three branch choices were: (1) Military Intelligence, (2) Medical Service Corps, and (3) Armor Branch.

Graduation

Advanced Camp was six weeks of extremes — heat, exhaustion, and relentless training. It pushed us to the edge, testing everything from basic soldiering to leadership under pressure. For me, it was life-changing: it forged resilience, cemented friendships, and gave me clarity about the path I would follow as a future Army officer.

When it was over, I graduated among the top five cadets out of the thousands at Advanced Camp — a recognition that validated the hard work, the sacrifice, and the determination it had taken to get there. More importantly, it marked the beginning of a professional journey that would carry me into greater challenges and responsibilities, shaping the course of my Army career in ways I was only beginning to imagine.