Chapter 14: First 24 Hours Under the Golden Dome

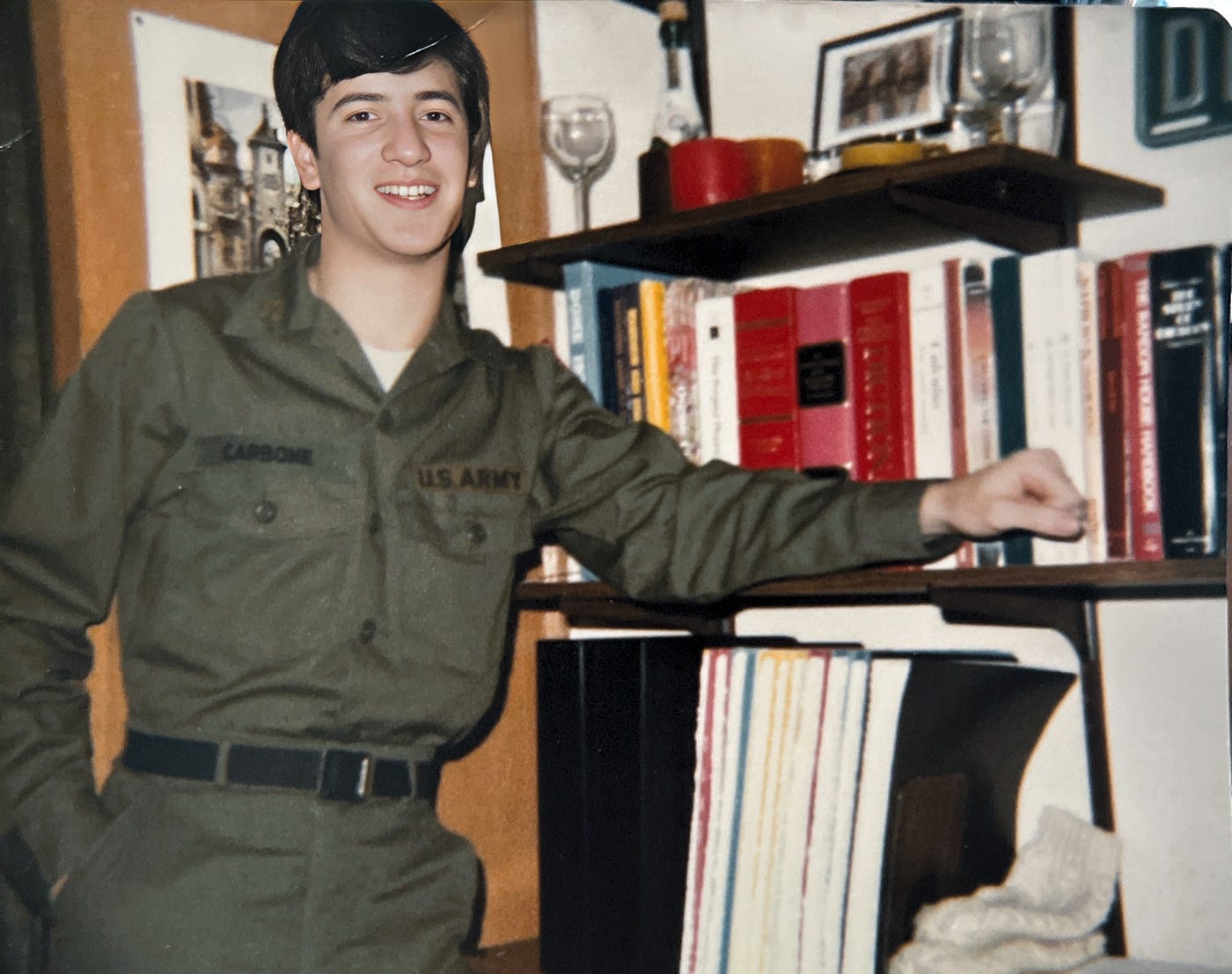

- Anthony Carbone

- Jul 22, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2025

BELIEVE NOTHING YOU HEAR, AND ONLY HALF OF WHAT YOU SEE — A Memoir of Service, Shame, and the Search for Truth

My New Home–Fisher Hall

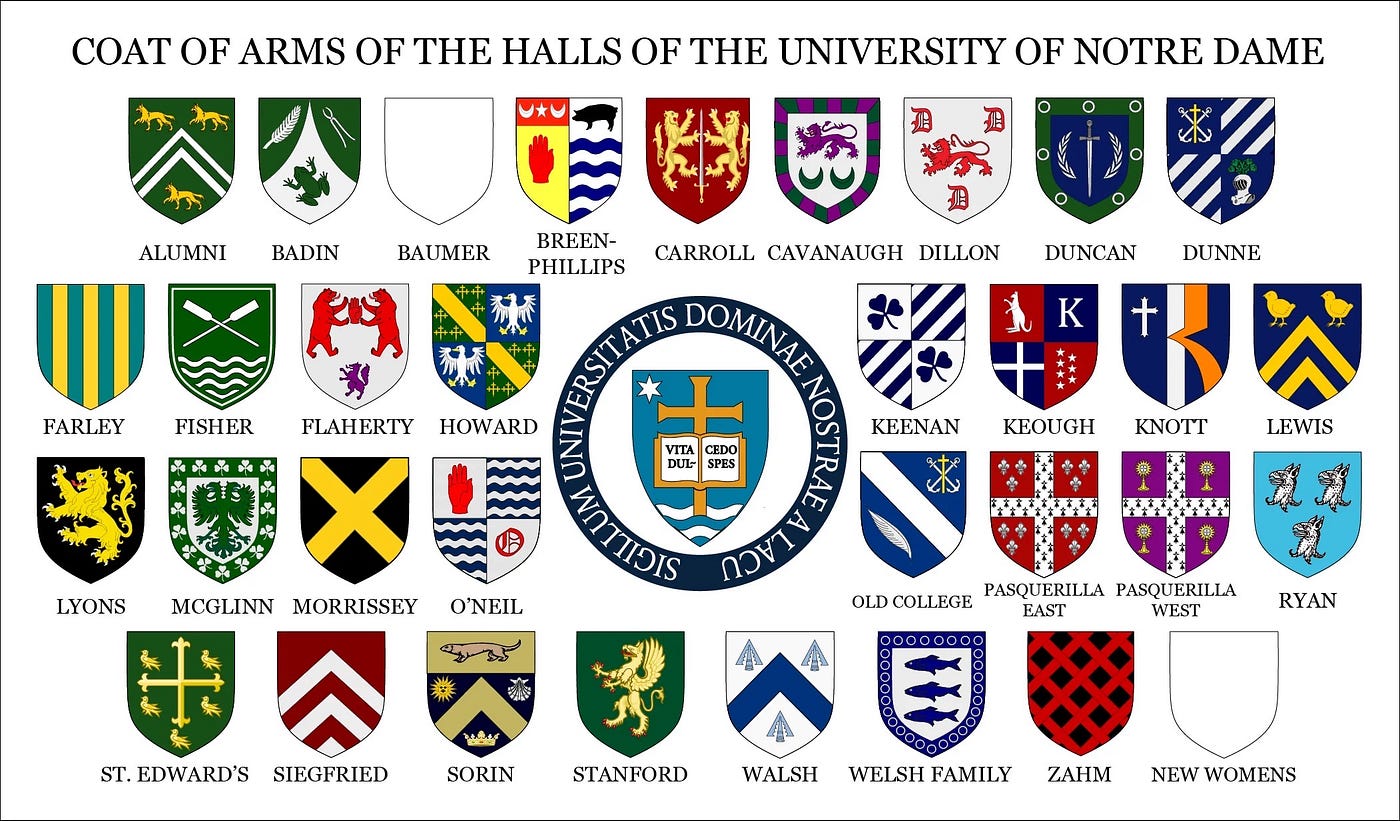

My father walked me over to my new home, Fisher Hall — one of Notre Dame’s newer and quirkiest dormitories. Not the historic, charming, ivy-covered palaces like St. Edward’s Hall or Dillon Hall. Fisher didn’t have mahogany paneling, grand staircases, or a dusty old library with secret corners. Rumor had it that the building had once housed religious sisters, and honestly, it looked the part.

Built with plain cinder blocks and lined with linoleum floors, it felt more like a high school hallway than something lifted from Oxford or Harvard. There was no Ivy League pedigree here. But it did have one coveted feature that made everyone else jealous: all single rooms. No bunk beds. No roommate drama. Just your own space — and in that sense, Fisher Hall was a kind of hidden treasure.

My Father’s Brief Goodbye

My father didn’t linger. No proud farewell speech. No long hug. Just a handshake and a nod. And then he was gone, and I was alone. I returned to my dorm room, and I stood there in the doorway of my tiny single room with just my one suitcase and nothing else but silence. No roommate was coming.

Atypical Notre Dame Freshman with Atypical Admission

Before I go any further, I should say something important: I was not your typical Notre Dame student. In fact, I had barely heard of Notre Dame before I applied. Actually, scratch that — I never really applied at all. That might sound impossible to believe, especially to people who grew up in South Bend or the Chicago suburbs, where Notre Dame is revered like a holy shrine.

But it’s true. I hadn’t grown up watching Fighting Irish football on NBC. Nor did I know the names of the dorm halls, the players, or any students who were attending. I came from a military family. We moved constantly. Our home base was Boston, and Boston has over 70 colleges and universities, including Harvard, MIT, and a number of famous Catholic colleges like Boston College. Notre Dame was a name I knew vaguely, but it wasn’t part of my world.

The Admission Essay

The average Notre Dame student, on the other hand, seemed to be born into the place. Their fathers had gone to Notre Dame. Their grandfathers. An uncle or two. Maybe an older brother already living in Dillon or Zahm, or Alumni Hall. They came in wearing ND sweatshirts they’d had since the fifth grade and carrying framed photos of the family tailgaters. When they found out I didn’t write an application essay, they looked at me like I had just admitted to skipping Confession.

“What did you write about on your admission essay?” they’d ask, curiously. “I didn’t write an essay because I wasn’t asked to provide one.” That was thanks in part to my story of going to a Department of Defense School in Europe, my class standings and SAT scores, and my four-year Army ROTC scholarship. I had been admitted through a separate channel, one that didn’t require me to jump through the traditional hoops. I never thought much about it. But I would quickly come to understand how elite and competitive Notre Dame was, how much it meant to be accepted, and how many doors people believed it opened.

Notre Dame Residential College System

It also meant that I didn’t know a thing about the school’s endless stream of traditions. And Notre Dame is built on tradition. The residential college system, for one, is nearly unique in the United States — modeled more on the University of Oxford in England than on your average American campus, which gave it that Ivy League atmosphere. Students are placed in a dorm their first year, and they usually stay there all four years. The dorm becomes your social center, your family, your identity. Greek life is nonexistent at Notre Dame — Catholic universities like this one typically forbid fraternities and sororities, seeing them as elitist or exclusionary. So your dorm is your fraternity. It’s your house, your flag, your tribe.

In that sense, Notre Dame was surprisingly similar to West Point — where I might have ended up if I hadn’t chosen this path. And in those first few days, adjusting to this foreign but rigidly structured environment, rules and traditions to quickly learn, it felt like Beast Barracks. A strange place. A complex system. A culture I hadn’t studied, but one I needed to figure out quickly, if I was going to survive.

Fisher Hall Charm and Eccentrism

Fisher Hall had its own charm, albeit untraditional— 150 single rooms, eighteen singles in my section alone, and each section had its own culture and cast of characters. Fisher’s single rooms seem to attract an eclectic group of guys, especially geniuses and jocks — and at Notre Dame, it was not unusual to find students who were both. My section included several new freshmen to include two pre-meds: me and Bob Terifay. We had our resident philosophy major, Matthew Bedics. A couple of engineers, including Andy Cordes and Al Emery, an architecture major, and Andy Entwistle, a government major. Our upperclassmen included several NCAA stars like premed football player Mike Calhoun (defensive tackle), Jerome Heavens (running back), and, most famous of all, Joe Montana — yes, that Joe Montana—future NFL legend and our quarterback who would go on to win the National Championship that fall, was my next-door neighbor.

Fisher Hall Celebrity–Joe Montana

New Freshmen Arrive with Their Families

That first afternoon, I watched from my door as the new freshman section-mates arrived with their families. They came in caravans, unloading what seemed like entire moving trucks full of stuff: lumber to build lofts, mini-fridges, televisions, rugs, stereo systems, full-blown furniture, posters, lamps, potted trees — yes, actual trees. They turned their dorm rooms into tiny kingdoms.

My New Dorm Room and Home

I stood there in my blank little barracks-like room, clutching my one suitcase and feeling like a foreign exchange student who had arrived with nothing but a passport and a toothbrush. My room looked like a cell. And I couldn’t help but feel envious — not just of the decorations, but of the closeness and excitement about Notre Dame that these families shared. My father’s goodbye had been swift, businesslike, and cold by comparison. Everyone else had a support team. I had… orders.

Over time, I would fix up my room and carve out a version of home inside those four walls: shelves with books and German beer steins and other souvenirs from Europe that reminded me of home in Bad Kreuznach and Heidelberg. I bought dark brown carpet, hanging plants, blankets, and bunches of eucalyptus that added to the familiar aroma of the Carbone home. But that first day, I was alone in an empty room and just felt like an outsider.

Most of my classmates were brimming with excitement — grinning, exploring, laughing with parents and siblings. Me? I was trying to figure out what exactly I was supposed to be so excited about. I was ready to study hard and begin military training — but to me, it all felt like work. Just work. My classmates seemed to know something I didn’t: that Notre Dame was a place of joy, tradition, and magic. I would come to see it too — but not yet.

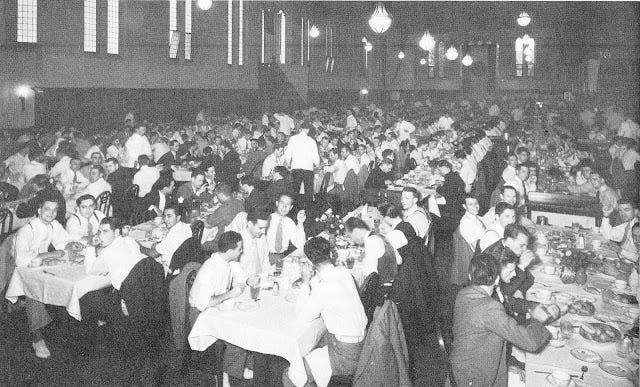

South Dining Hall

That night, most freshmen went out to dinner with their families and ended up sleeping in the hotels with their families. I wandered down to the South Dining Hall on my own. I always called it the “Mess Hall”, out of habit. That’s what it reminded me of — except with far more beauty, history, and civility.

The place was stunning. A gothic cathedral of food. Vaulted ceilings stretching possibly 50 feet high. Stained glass windows filtering the golden dusk. Long oak tables arranged like a medieval feast. It felt like something out of Harry Potter, long before Hogwarts had been imagined.

The food was hot and hearty — roasts, fresh vegetables, warm rolls. But it was the women behind the counter who stood out most. Older, warm, motherly. The kind who called you “Son” and gave you an extra scoop of mashed potatoes if they thought you looked too skinny. I used to joke to myself that the only job requirement was: must be a Polish grandmother who lost a son in the war.

I ate alone that night, watching the swirl of happy students around me, and tried to study the system — where to find the trays, where to drop off your dishes, what tables were open, and which ones were “taken.” Everything felt like a puzzle. But I was swept up in the history of the university and the ghosts of students past who had eaten their meals here in the old South Dining Hall.

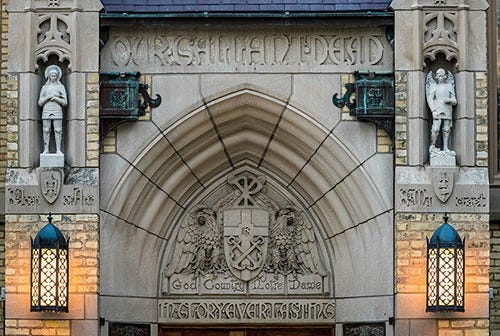

The Golden Dome–Administration Building at Notre Dame

After dinner, I went walking. The sun was low in the sky, and the evening air was cool. I couldn’t help but make my way toward the heart of campus — the University’s most iconic symbol — the Golden Dome atop the Main Building. As twilight settled over South Bend, the dome shimmered in the fading sunlight, radiating a warm, almost heavenly glow. I had seen pictures, sure — but standing there in person was something else entirely.

The real gold leaf that coated the dome caught every last ray of light, casting a halo over the campus. Atop it all stood a 19-foot-tall, 4,000-pound statue of Mary, the Mother of God, arms outstretched, as if blessing all who passed beneath her. I didn’t yet know the full history — that the dome had originally been painted white, destroyed by fire in 1879, then rebuilt and regilded many times since, most recently in 2023 — but I could feel the weight of that history just standing there.

Inside the Administrative Building

I climbed the front steps and pushed open the heavy doors of the Main Building. Inside, I was immediately overwhelmed. It was magnificent — like walking into a cathedral of learning.

The mahogany-paneled walls glowed with polish and age. Massive staircases spiraled upward like something out of a Gilded Age mansion. And on the walls hung enormous historic murals — depictions of explorers, saints, and scholars that seemed to breathe with meaning. This wasn’t just an administration building. It was a shrine to the university’s mission, to its faith, and to the vision of its founder, Father Sorin, who had dreamed of building a great university in honor of Our Lady. I had felt out of place for most of the day. But here, under the Golden Dome, I felt something new: reverence. And maybe, just maybe, a sense that I belonged.

Basilica of the Sacred Heart

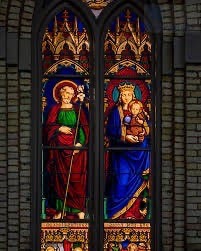

My next stop was the Basilica of the Sacred Heart — Notre Dame’s main church and one of the most awe-inspiring buildings I had ever stepped inside.

The Basilica is the spiritual center of the campus, both historically and physically. Its stained glass windows alone are legendary — the largest collection of 19th-century French stained glass outside of France, crafted by Carmelite nuns in Le Mans. The colors glowed like jewels in the candlelight.

The carvings, the gold, the silence — it was the first time since Europe that I had seen such sacred beauty. It felt holy. Not just as a church, but as a space where something deeper pulsed. I couldn’t wait to attend Mass there.

Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes at Notre Dame

And I wasn’t done walking. I found my way toward the woodsy end of campus, past the bookstore (already closed), and finally, to the most sacred place of all: The Grotto.

Nestled into the hillside, the Grotto is a one-seventh scale replica of the famous shrine at Lourdes, where the Virgin Mary appeared to Saint Bernadette. Father Edward Sorin, Notre Dame’s founder, had visited Lourdes and felt compelled to bring its spirit home to South Bend. The Grotto he built became a place of prayer and pilgrimage for generations of Notre Dame students. And from that very first night, it became my place too.

Hundreds of candles flickered in the dusk, casting shadows on the stones. It was silent, sacred, and impossibly peaceful. I knelt, lit a candle, and said my first prayer as a Notre Dame student. Please, God, let me become a doctor.

That became my nightly ritual. For four years, I would visit the Grotto almost every single night. No matter how stressful the day, no matter how many exams or drills or sleepless nights, I would return to that spot, light a candle, and pray. Even in the coldest of blizzard nights.

Saint Mary’s Lake

After I spent some time at the Grotto, I wandered farther down the winding paths and found myself standing at the edge of a still, glistening lake — Saint Mary’s Lake. The reflection of the trees and sky on the water’s surface was breathtaking. I paused there for a long time, alone with my thoughts, overwhelmed by the sense of history and sacredness that seemed to rise from the very ground beneath my feet.

I later learned that this same lake was what captivated the French missionaries who founded the university. In 1842, Reverend Edward Sorin and his companions from the Congregation of Holy Cross arrived here from France. Struck by the natural beauty of the lake and the surrounding land, they chose this spot to build a school dedicated to the Virgin Mary. That’s why the university’s full name is Notre Dame du Lac — Our Lady of the Lake. Knowing that made the place feel even more special, as if I was now part of a story that had started long before me.

Subsequently, I made my way back to Fisher Hall. It was eerily quiet. Most freshmen were out at restaurants or hotels with their families. I crawled into bed in my tiny single room, listening to the old radiator click and groan, and stared at the ceiling in the dark. I had no idea what the coming days, weeks, or months would bring. However, I was here — and I was ready.