Chapter 23: Chemical Officer Basic Course at Fort McClellan, Alabama (June — October 1981)

- Anthony Carbone

- Sep 16, 2025

- 11 min read

BELIEVE NOTHING YOU HEAR, AND ONLY HALF OF WHAT YOU SEE — A Memoir of Service, Shame, and the Search for Truth

Orders for the U.S. Army Chemical School at Fort McClellan, Alabama

Before I was officially commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Chemical Corps, I received official orders to attend the Chemical Officer Basic Course (COBC) at the U.S. Army Chemical School at Fort McClellan, Alabama. I was to report for dury in June of 1981.

U.S. Army Chemical Officer Basic Course

My four+ months at Fort McClellan for the U.S. Army Chemical Officer Basic Course (COBC) were a crucible — technical schooling wrapped tightly around culture shock, misadventure, and lessons that have never left me. The Chemical Officer Basic Course gave Chemical Corps lieutenants the skills to face some of the most terrible weapons humans can make; the life off-post gave me the stories I still tell.

Reporting to Fort McClellan

I was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Chemical Corps and ordered to Fort McClellan, Alabama, in June 1981 to attend the Chemical Officer Basic Course. I didn’t own a car yet, so I stuffed a duffel with fatigues, combat boots, my Class A uniform, a few civilian clothes, and a shaving kit, flew from Boston to Birmingham, then took a bus to Anniston and onto post. Fort McClellan housed the Chemical School and the Military Police School — two corps that loved to needle each other — and had once been the home of the Women’s Army Corps until it was disbanded in 1978. When I arrived, it felt like me and 10,000 other men.

BOQ Life and My Roommate, Rich

We were billeted in the Bachelor Officer Quarters (BOQ): small one-man rooms with a bed, a desk, a closet, and a shared bathroom. My next-door roommate was Rich, a tall, thin Virginia Military Institute (VMI) grad and former Chinook pilot. He was older, knew a lot about Army life already, and became a mentor to me. Rich was generous with advice, persuasive in plans, and a fixture in the stories that followed.

TDY Pay, Ramen, and Buying My First Car

While on TDY (Temporary Duty) we received a little extra pay. Rich and I saved every penny and ate commissary Ramen — ten cents a pack — to keep our bank accounts growing. One Saturday we took a taxi into Anniston to look at cars. Rich drove off the lot in a Datsun 280ZX; I bought a Plymouth Sapporo (a Mitsubishi in disguise). Rich convinced me to get the 5-speed even though I’d only learned to drive stick a week earlier on a quarter-ton jeep. I was hesitant, but the idea of freedom won out.

The Sapporo Lasted One Day

On the scenic route back to post, Rich led us through Talladega State Park and drove his new Z like he imagined he was in a race. I tried to keep up. Around a sharp bend, a narrow bridge with concrete sides appeared suddenly. Before I registered what was happening, I slammed my brand-new car into the concrete barrier. The Sapporo was totaled before I had even made it back to Fort McClellan.

Worse, in 1981 you didn’t have to have insurance to drive a car off the lot. The tow truck hauled the wreck away while Rich and I returned to the BOQ stunned. I made the most awkward call of my young officer life to USAA:

“Ma’am, this is Lieutenant Carbone. I bought a new car today.” “Congratulations, Lieutenant!” she replied cheerily.“Yes, ma’am. I have a bit of a problem — I totaled my new car on the way back to post and didn’t have a chance to call for insurance yet.”After a short pause she said kindly, “Oh, Lieutenant. Don’t worry. USAA will cover you.” I’ve been a USAA customer since that day.

The Grind: PT, Road Marches, and the First Month

The course itself began as a grind. PT before dawn, long runs, and road marches with full kit. At times it felt more like Ranger School than a technical branch course. We learned to lead, to plan, and to sweat — a lot — in the Alabama heat. Every day was about sharpening skills that had to become reflexive. The hardest part was that we seemed to be receiving the same training as infantry lieutenants did, but we were doing it with suffocating gas masks and protective gears and gloves. It was brutal in the hot, humid Alabama summer.

Security Clearances and the Top-Secret Briefing (Saddam Hussein)

Roughly a month in, our Captain announced our security clearances had come through. Twenty-five Chemical Corps lieutenants signed non-disclosure forms and were shepherded into a small auditorium. The lights dimmed and a film began.

Learning About Saddam Hussein

We were introduced to a man most of us had never heard of: Saddam Hussein, the ruthless dictator of the Iraq Republic.

The film showed footage of Iraqi forces using chemical agents against Kurdish civilians — scenes of men, women, and children dead or dying, skin a strange dark-purple color, mouths and eyes frozen wide open. It was a nightmare that burned itself into the back of my mind.

The intelligence officer’s message was blunt: “Gentlemen, this is Saddam Hussein. He is murdering Kurds with poison gases and building up his chemical warfare capabilities to fight Iran. We are not prepared. You have been assigned to the Chemical Corps to help prepare our forces to deal with this new threat.”

Saddam Hussein's Chemical Weapons Program

When you do internet searches on the use of chemical weapons by Iraq, it says it started in 1983 against Iranian troops, with the infamous civilian attack known as The Halabja Massacre occuring on March 16, 1988. But I know what I was shown that summer in 1981. It was the very beginning of the horror to come.

Efforts by Iraq to acquire chemical weapons dated back to the early 1960s, driven by the desire to strengthen its military, especially after the 1973 Arab–Israeli War. But it was not until Saddam Hussein came to power that the program gained steady momentum. At the time of Iraq’s invasion of Iran in 1980, the country had no significant stockpiles. Yet, within months, Saddam’s regime launched intensive research and production efforts, rapidly building up its chemical corps and chemical arsenals. Battlefield use during the Iran–Iraq War became both a weapon of terror and a live test of Iraq’s growing chemical warfare capabilities.

That briefing changed everything. The denied educational-delay requests suddenly became clear: the Army needed chemical officers to lead a new Chemical Corps now.

Mission of the U.S. Army Chemical Corps

During the 1980s and 1990s, Fort McClellan’s training missions largely dealt with U.S. chemical and biological warfare and reducing stockpiles of chemical agents. The Chemical Corps at Fort McClellan increased its training to provide each U.S. Army unit with its own chemical specialists to maintain their expertise in treatment and decontamination in case of chemical, biological, or radiological attacks.

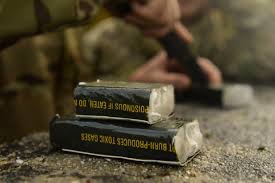

Live-Agent Training

The Chemical Decontamination Training was the centerpiece of the course — a sterile, bunker-like chamber where controlled amounts of live nerve agents could be introduced for confidence drills. We were briefed, suited up in full MOPP, and ushered into the chamber. The most dreaded drill was being told to break the seal on your mask for a second so you could feel the agent. The effect was immediate: your eyes burned, your throat stung, and panic surged until you cleared and resealed the mask. Those seconds taught a lesson no classroom could: the mask and decontamination procedures were literally the difference between life and death.

Helicopter Rides — A Breath of Freedom

Whenever Army aviators needed flight hours I snagged a ride. Strapping into a helicopter, sliding on a headset, and watching the Alabama quilt below felt like a prize after long days in class and the claustrophobic hours in MOPP suits. Those flights were small freedoms that kept us sane.

The Nuclear Training Exercise

We trained for nuclear contingencies: decontamination lines, fallout prediction, and casualty handling. Standing in full MOPP, weighed down by layers of protective gear, Geiger counter by my side, I stared at maps and calculations, imagining blast radii and contaminated terrain.

Using military calculators and compasses under the relentless heat and bulk of the suits was grueling. Every second counted as we calculated wind directions and predicted fallout, racing against time to give commanders guidance on how to maneuver safely. It was clinical, precise, and exhausting — a sobering rehearsal for horrors we hoped would never come to pass.

Learning to Drive the Army’s Motor Pool

The school wanted us useful in any situation, so we learned to drive nearly everything in the Army’s inventory. We started with the M151 Truck, Utility, ¼-Ton, 4x4 — the old Jeep with independent front and rear axles that made it highly maneuverable but prone to tipping. Backing a Jeep with a trailer — where the rear wheels move independently of the front — was an exercise in patience and profanity.

From there we graduated to the 1¼-ton truck, the 2½-ton “Deuce and a Half,” and the 5-ton. We handled the M561 Gamma Goat — a six-wheel articulated piece of machinery that seemed to defy logic — the M113 armored personnel carrier, and, to my astonishment, I even had the opportunity to drive an M60 main battle tank. By the end, I held licenses for more Army vehicles than I could have imagined.

Flame & Explosive Training

My favorite area of training was flame and explosives. The explosives range had bleachers with a corrugated aluminum roof overlooking a field dotted with bunkers built from huge timber ties. We learned to use detonation cord (det-cord, civilian primacord), which looks like green plastic clothesline but contains a PETN explosive core — wrap it around a tree four times and it will slice the tree in half when detonated. We trained with C-4, blasting caps, and the craft of incendiaries like napalm.

All About Napalm

The instructor told us firing napalm was optional. My 24 classmates climbed into the bleachers to watch. I did not opt out. We were taught how to make napalm using diesel fuel and thickening agent, and then to let it age to improve its stickness.

The “Wall-of-Flame”

Given three 50-gallon drums of aged napalm, I constructed what we called the “Wall-of-Flame.” We dug a knee-deep, 20-meter trench and laid five or six lines of det-cord along the base. The instructor and I poured 150 gallons of napalm into the ditch and covered it with dirt. At the end of the det-cord we attached a military sparkling flare. The explosives sergeant and I took cover in a safety bunker, I fed the free end of the cord into an M57 ignition device, yelled, “Fire in the hole!” three times and squeezed the clacker.

The det-cord detonated. Napalm shot at least 100 meters skyward and the sparkler ignited it. Blobs of burning napalm flew everywhere — some landed on the corrugated roof of the bleachers and the timber bunkers caught fire. My classmates screamed and scattered. Fire trucks were called to douse the flames.

When the smoke cleared, the explosive instructor smacked me on the back and said, “That was AWESOME, LT!” He gave me a high-five and declared me the Honor Grad of the course. That day I became, in the instructor’s eyes, a flame and explosives expert — a skill set I would use extensively when I reached my first permanent unit.

Life in the Deep South (1981): Wayne, the Hibachi, and Denny’s

I’d grown up during the Civil Rights era and gone to integrated schools in Germany; I believed much of that ugliness was behind us. Alabama in 1981 taught me otherwise. Driving around Anniston, I’d stop at gas stations with two weathered bathroom doors — Whites and Coloreds. That visual struck me as a harsh echo of a past I thought was fading. Locals, Black and White, often acted as if it were ordinary.

One Saturday night, all twenty-five lieutenants went to a Japanese hibachi restaurant near post. Wayne — a huge, jolly African-American lieutenant with dark skin, a huge smile, and a laugh to match — sat beside me. The chef theatrically ladled sauces and chanted, “Secret sauce… secret sauce… secret sauce.” When he reached Wayne he grinned and said, “Ketchup!” Later, passing shrimp: “Shrimp… shrimp… shrimp” — and to Wayne: “Catfish!” I was appalled. Wayne roared with laughter.

While we ate a mouse scampered by my shoes and I reflexively lifted my feet. The waitress slapped my knees jokingly and scolded, “Put feet down! You big baby! Afraid of little mouse? You officer?!” Wayne laughed at me — and with me.

Another weekend Wayne and I and two of our classmates went to Denny’s. The waitress set down three glasses of water and three menus, omitting Wayne. I began to boil with anger and disgust. I demanded to see the manager and later reported the incident to the post commander. That Denny’s was placed on the Off-Limits List. Some time later, the Federal Government sued the chain for discrimination. For me, it was a painful lesson: the Army might aim for equality, but some towns still carried old wounds.

A Weekend Trip to Pensacola (R&R)

We earned a weekend off and four of us — Rich, Perry, another lieutenant, and I — piled into Perry’s jeep and headed for Naval Air Station Pensacola. The landscape felt like the Mark Twain South I’d read as a kid: shanty, shanty, shanty, then suddenly an antebellum mansion, with cotton fields in between.

Gas Station Stop

We stopped at a one-pump gas station with a little general store attached. While Perry filled the jeep, I went inside to buy a Coca-Cola. Behind the counter was an old man who squinted at me and mumbled, “Foryee? “Excuse me, sir?” I asked politely. “Foryee!” he barked again. I was completely confused. “I’m sorry, sir, what did you say?” This time he shouted, “Foryee, God dammit!”

I panicked and yelled out the door, “Perry! Get in here!” Perry ran inside, and I quickly threw an arm around his shoulder and said, “Ask him!” The old man looked at Perry and repeated in a calmer voice, “Foryee?” Perry burst out laughing. “What can he do for you?”

It finally clicked. I turned back to the old man and apologized, explaining that I was an Army officer from out of town and only wanted a Coca-Cola. He sold me one, Perry finished filling the tank, and we left laughing about my ignorance of the Southern drawl.

Diner & Junior Miss Alabama

Farther down the road, we stopped at an old diner with a counter lined with red leather stools. Behind it stood a cheerful older man who looked us over and said, “You boys be officers.” I asked how he could tell, and he pointed to an Army cap with First Sergeant stripes hanging on the wall. “It’s nice to meet you, First Sergeant,” I said. “The four of us are looking for some chow.”

“Sit down, Lieutenants,” he said warmly, popping open four green glass bottles of ice-cold Coca-Cola and handing us menus. Then he grinned. “You want some entertainment?” We looked at each other and said, “Sure.”

He turned and hollered, “Mary Jane Sue Ellen! Get your butt in here!” A skinny redheaded girl with braids, a red polkadot dress, and a white apron came running in, sliding to a stop. “Yes, Pa?” “Mary Jane Sue Ellen, these boys be officers. Do your talent for them.” “Yes, Pa.” She snapped to attention, presented arms with a perfect salute, and declared, “America! Love it, or leave it!” Then she launched into a tap dance routine right there on the diner floor.

I sat at the counter with tears running down my face from laughing and sheer amazement. The First Sergeant beamed with pride. “Gentlemen, my little girl is going to be a contestant in the Junior Miss Alabama Pageant. I hope you’ll pray for her.” “Of course we will, First Sergeant,” we assured him. We finished our burgers and fries, drained our Cokes, and continued on to Pensacola.

Naval Air Station Pensacola

At NAS Pensacola I took out my camera to photograph F-14 Tomcats on the tarmac. A Navy jeep converged on us and Master-At-Arms (MPs) jumped out with M-16s leveled. “Who are you and what are you doing?” they barked. Hands up, I said, “We’re U.S. Army lieutenants from Fort McClellan, on leave.”The petty officer warned me it was unauthorized to photograph military aircraft. Lesson learned.

Graduation and Airborne Orders

After over four months of intense, exhausting, and unforgettable training, it was time for graduation. I was proud to finish as an Honor Graduate. At the ceremony, four of us — including me — received orders to report immediately to Fort Benning, Georgia, for Airborne School. Our Chemical Corps journey was about to continue, and this time the training would start from the sky.