Chapter 3: A New Airborne Officer's Career

- Anthony Carbone

- Jul 22, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Sep 5, 2025

Believe Nothing You Hear, and Only Half of What You See—A Memoir of Service, Shame, and the Search for Truth

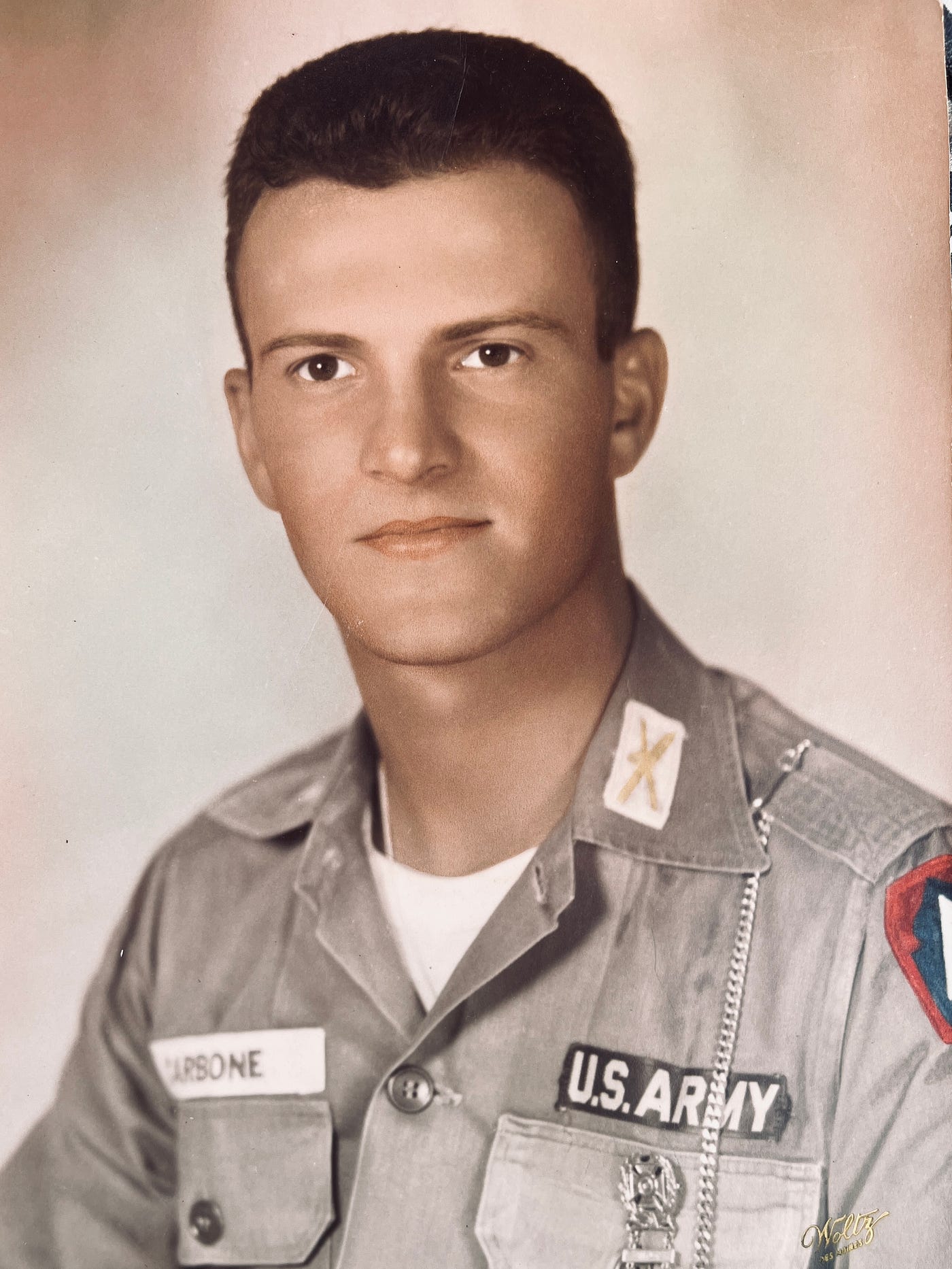

Army Commissions Father a Cavalry Lieutenant

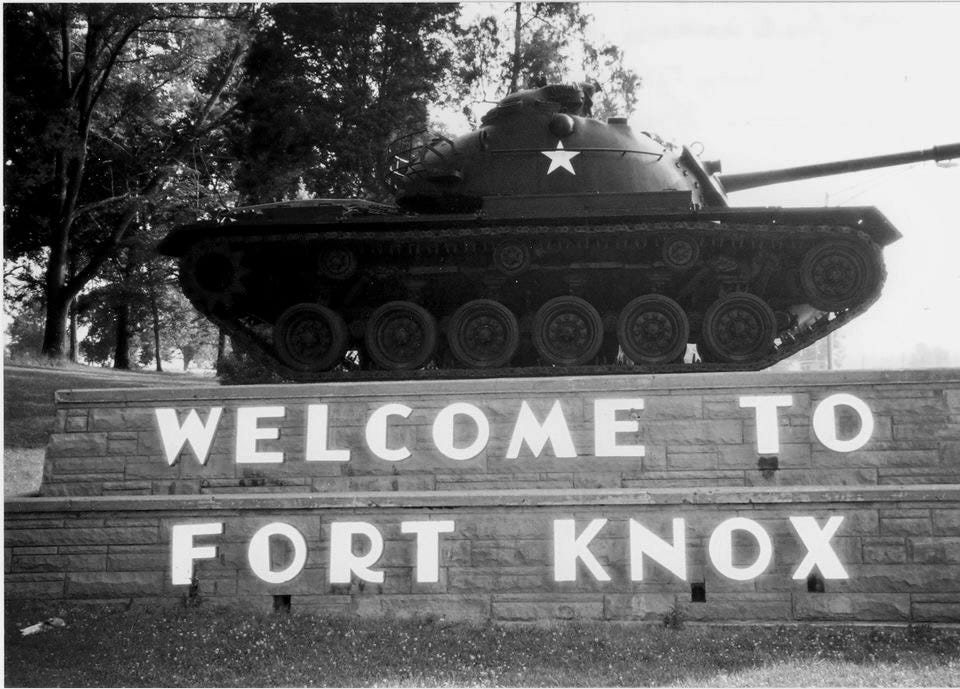

Father Receives Orders for Fort Knox, Kentucky

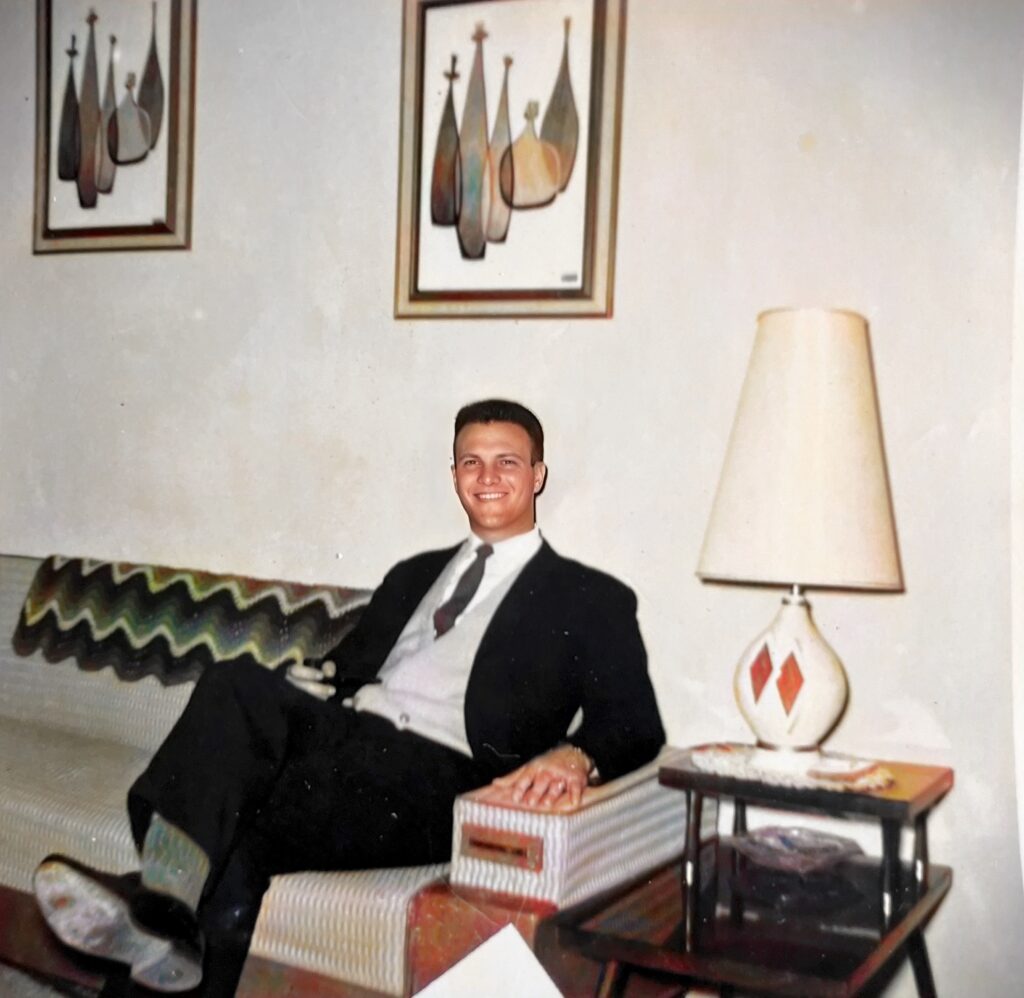

After graduating from Norwich University on December 18, 1958, the President of the United States commissioned my father into the United States Army as a Cavalry Officer. His first assignment brought him and my mother to the U.S. Army Armor Officer Basic Course at Fort Knox, Kentucky. The Army designed this several-month training program to transform him from a generalist cavalry officer into a specialist in armor and mechanized warfare.

We lived in a modest government house nestled in the company grade officer neighborhood of Fort Knox during that time. Though the housing was simple, it felt more spacious and comfortable than the trailer we had come from in Missouri. For my mother, this was a slight reprieve — finally, a bit of stability while my father threw himself into his next round of training.

Father Receives Orders for Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri

After completing the Armor Officer Basic Course at Fort Knox, my father received orders to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, in 1959, where the Army put him in charge of a training platoon. It was the beginning of his official military career — an ideal soldier stepping into the long shadow of duty, discipline, and sacrifice.

Family Living Off-Post in a Tiny Trailer in Missouri

But for my mother, this period was anything but glamorous. She moved into a tiny trailer off base with my two sisters, Lynne and Diana. The trailer had no telephone, no car, and very few luxuries. Isolated in rural Missouri and far from her family in Medford, Massachusetts, my mother often described those early days as some of the most difficult in their marriage. It was a time of intense homesickness and growing pains — where she began to understand what it truly meant to be an officer’s wife.

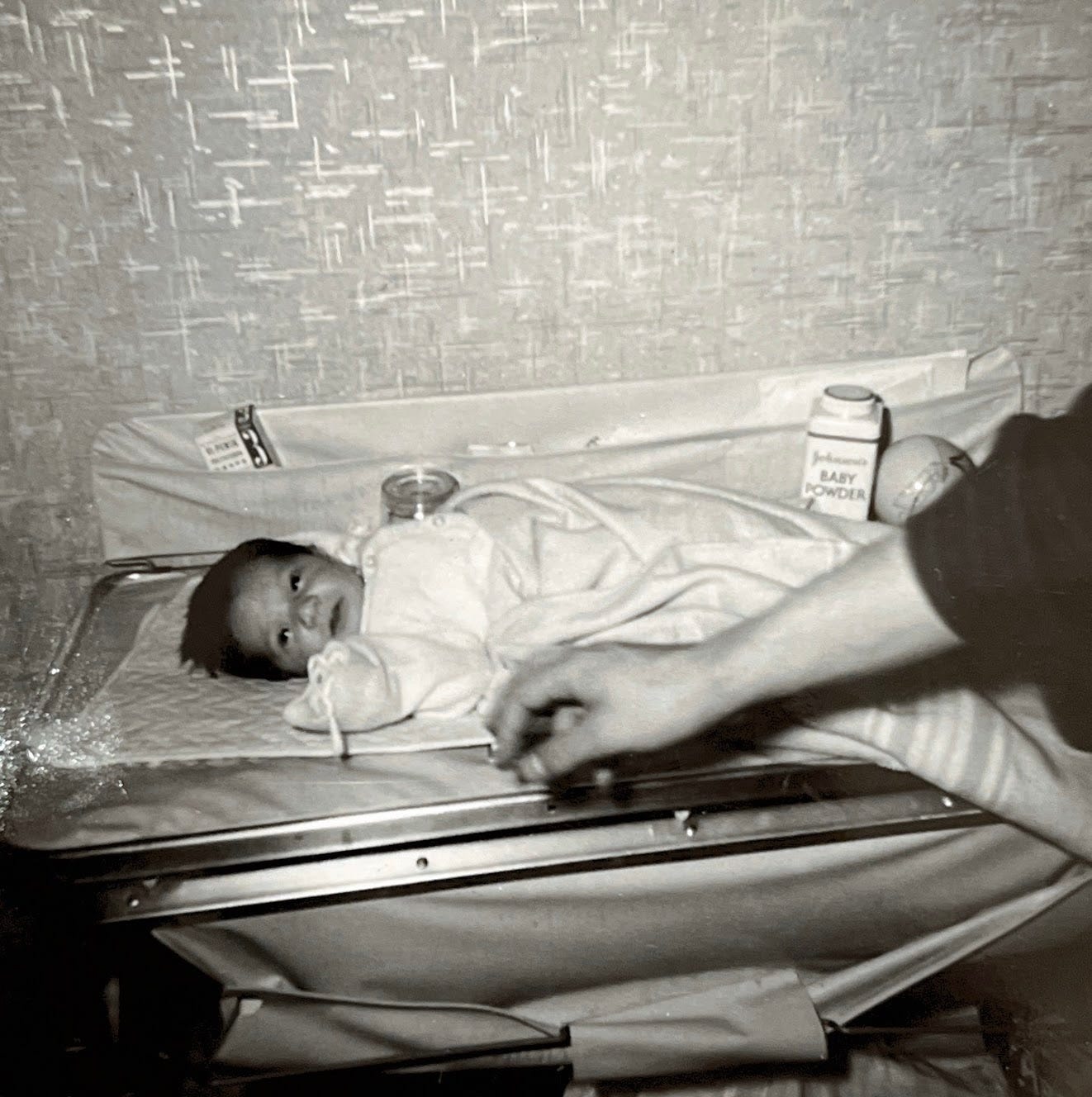

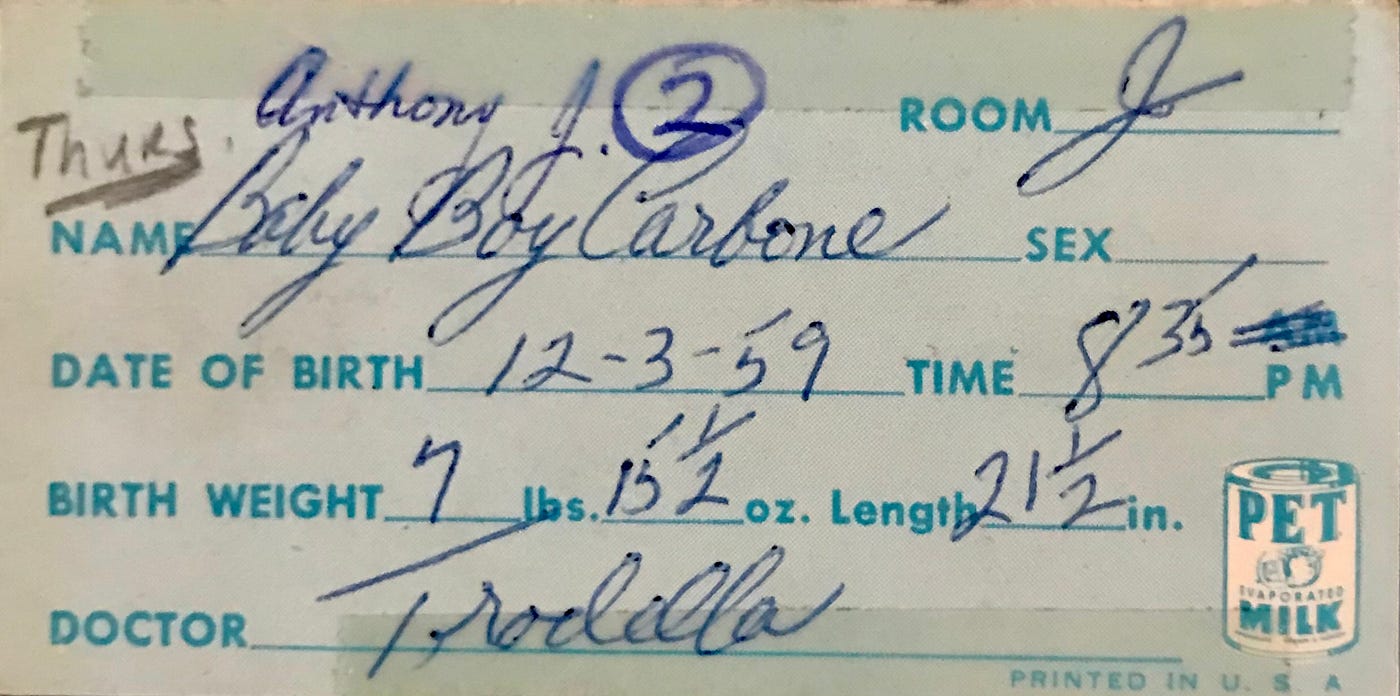

My Birth, December 3, 1959

In the winter of 1959, my mother made a brave decision. Wanting to be close to her family and the familiar care of her longtime doctor, she traveled alone — with no car and no support from the Army — back to Medford, Massachusetts, to give birth to me. My father remained on duty at Fort Leonard Wood, unable to accompany her. I was born on December 3, 1959, at Lawrence Memorial Hospital, delivered by Dr. Trodella — the same physician who had brought my sisters Lynne and Diana into the world. Not long after my birth, my mother bundled up her newborn son and returned to Missouri, where our now family of five squeezed back into the same little trailer.

My Mother’s Younger Sister Greyhound from Boston to Missouri Alone

Then a story about my aunts and Fort Leonard Wood always surprised and impressed me. My mother’s younger sisters — Norma, Cynthia, and Yvonne — decided to visit her all the way from Boston. They didn’t have much money, and none of them had ever traveled so far. But they pooled what they had, boarded a Greyhound bus, and rode all the way across the country to rural Missouri.

This was long before mobile phones or even reliable landlines. When they finally arrived, they sat at the local bus station for hours, waiting patiently for my father to get off duty and pick them up. During their visit, there were now eight people living in that little trailer. My mother described it as cramped and chaotic, yet she said it was one of the most joyful and loving visits of her life. Laughter, babies, stories, and sisterhood filled that small space, reminding all of us that even in humble surroundings, family makes room for family.

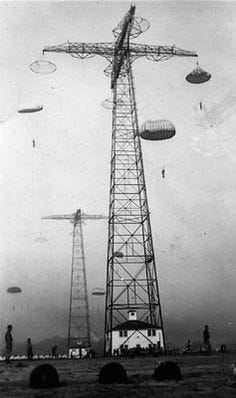

Father Sent to Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia

Upon completion of his assignment at Fort Leonard Wood in 1960, my father received orders to attend paratrooper training at the U.S. Army Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia. Over the course of three grueling weeks, he trained relentlessly to earn the coveted silver paratrooper wings. The jumps were real. The risks were real. My father stood determined and proud when he completed the course and became a paratrooper, a distinction he carried with pride for the rest of his life.

Father Receives Orders for 10th Cavalry Regiment in Korea

Shortly after completing his airborne training, my father actively served a year-long unaccompanied tour in South Korea from 1960–1961, leading as a Cavalry Platoon Leader and Squadron Adjutant with the 10th Cavalry Regiment. I have photographs of him wrapped in his heavy Army-issue extreme cold weather parka and wearing those oversized insulated “Mickey Mouse” boots designed for sub-zero conditions. The images showed him standing beside tanks that had slid off icy roads and flipped completely over in the snow — gritty proof of the harsh terrain and rugged conditions he endured.

My godfather, Uncle George, stepped in to help

During that year, while my father braved the Korean winter, I was just one to two years old, too young to understand his absence but old enough to feel its impact. My godfather, Uncle GeorgePietrantoni, only about 18 at the time, stepped into the void, becoming a familiar presence in my life. But when my father returned, I had entered the “Stranger-Danger” phase of childhood, wary of unfamiliar faces — even his. My instinctive withdrawal stung him deeply, planting the seeds of an awkward tension that lingered between us for years, a quiet rift neither of us fully knew how to bridge.

We Live With Nana Pietrantoni

While my father served in Korea, my mother brought us back to our haven in Medford, Massachusetts, to live at my nana’s house. That house, a bustling three-story home, was our true home away from home. My grandparents lived on the second and third floor, along with my nana’s sister, my great aunt Concetta, three of my mother’s sisters (Aunties Norma, Cynthia and Yvonne), and eventually — my mother and her three children. The house was always alive with movement and voices. Family members came and went in a constant stream, and my nana seemed to be cooking from sunrise to midnight. The smell of garlic and fresh tomato sauce filled every hallway. My papa was always in the backroom sewing on his vintage Singer sewing machine with a rhymthic chucka sound. It was noisy, crowded, and warm — and to me, it was the safest place on earth.

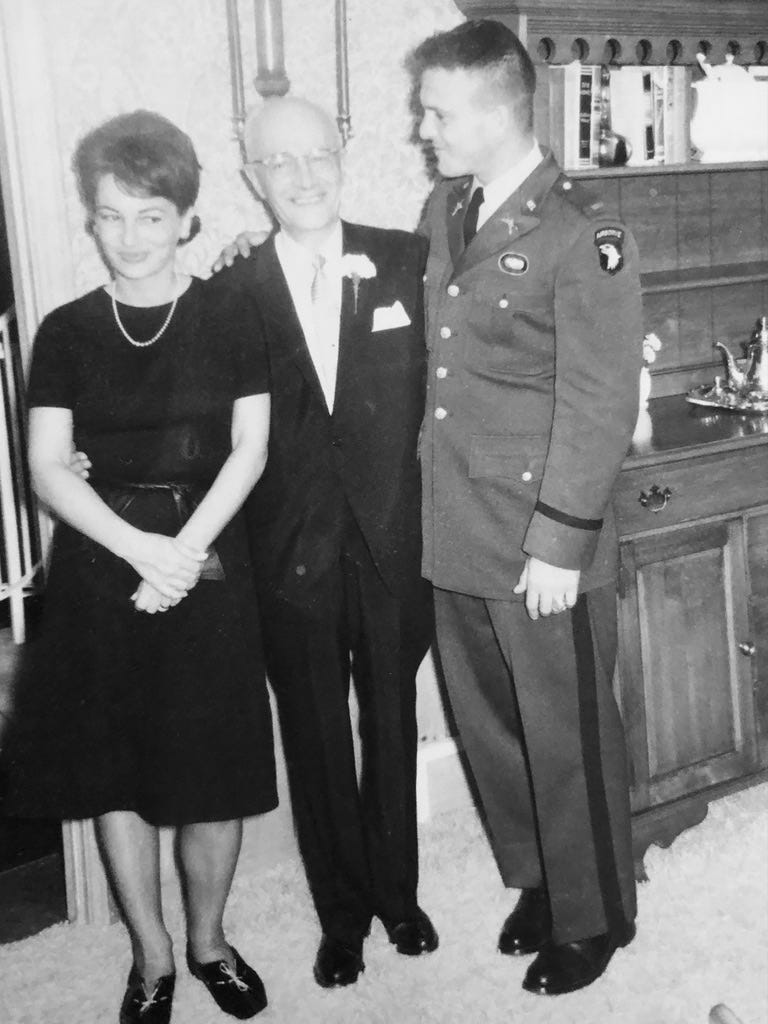

Father Receives Orders for 101st Airborne DIvision at Fort Campbell, Kentucky

After completing his tour in Korea, the Army sent my father to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he served from 1961 to 1963 with the prestigious 101st Airborne Division, the “Screaming Eagles.” He served as the Adjutant for the Headquarters and Headquarters Company of the division. Once again, our family lived in government quarters on post, adjusting to the routines and rituals of a new Army installation.

The Cuban Missile Crisis

During this same period, in October of 1962, the United States faced one of the most dangerous confrontations of the Cold War — the Cuban Missile Crisis. This 13-day standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union began when American reconnaissance aircraft discovered that the Soviets were installing nuclear missiles in Cuba, just 90 miles from Florida. President John F. Kennedy responded by ordering a naval blockade of the island and demanding the immediate removal of the missiles. For nearly two weeks, the world stood on the brink of nuclear war. Thankfully, U.S. and Soviet leaders eventually resolved the crisis through diplomacy, though only after extraordinary tension and heightened military readiness.

Dad and the 101st Airborne Prepare to Invade Cuba

Most history books record that elite Army units, including the 101st Airborne Division, were mobilized and staged in Florida and Georgia in anticipation of a possible full-scale invasion of Cuba. However, what most people don’t know — and what I know from my own father’s account — is that he was part of a classified mission to Puerto Rico. As the Adjutant for the Command & Control Battalion of the 101st Airborne Division, he and a select group of officers were quietly deployed to Ramey Air Force Base in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, during the height of the crisis. Their presence there was never officially acknowledged in the open-source historical record, but it’s part of our family’s private history.

I remember overhearing fragments of the story growing up — how the tension was palpable, the operation strictly need-to-know, and the mood deadly serious. My father never glorified the moment, but the fact that he was trusted to be part of such a critical, behind-the-scenes operation speaks volumes about the kind of officer he was becoming. The Cuban Missile Crisis may have been narrowly avoided through diplomacy, but my father and others in the 101st were prepared to act at a moment’s notice.

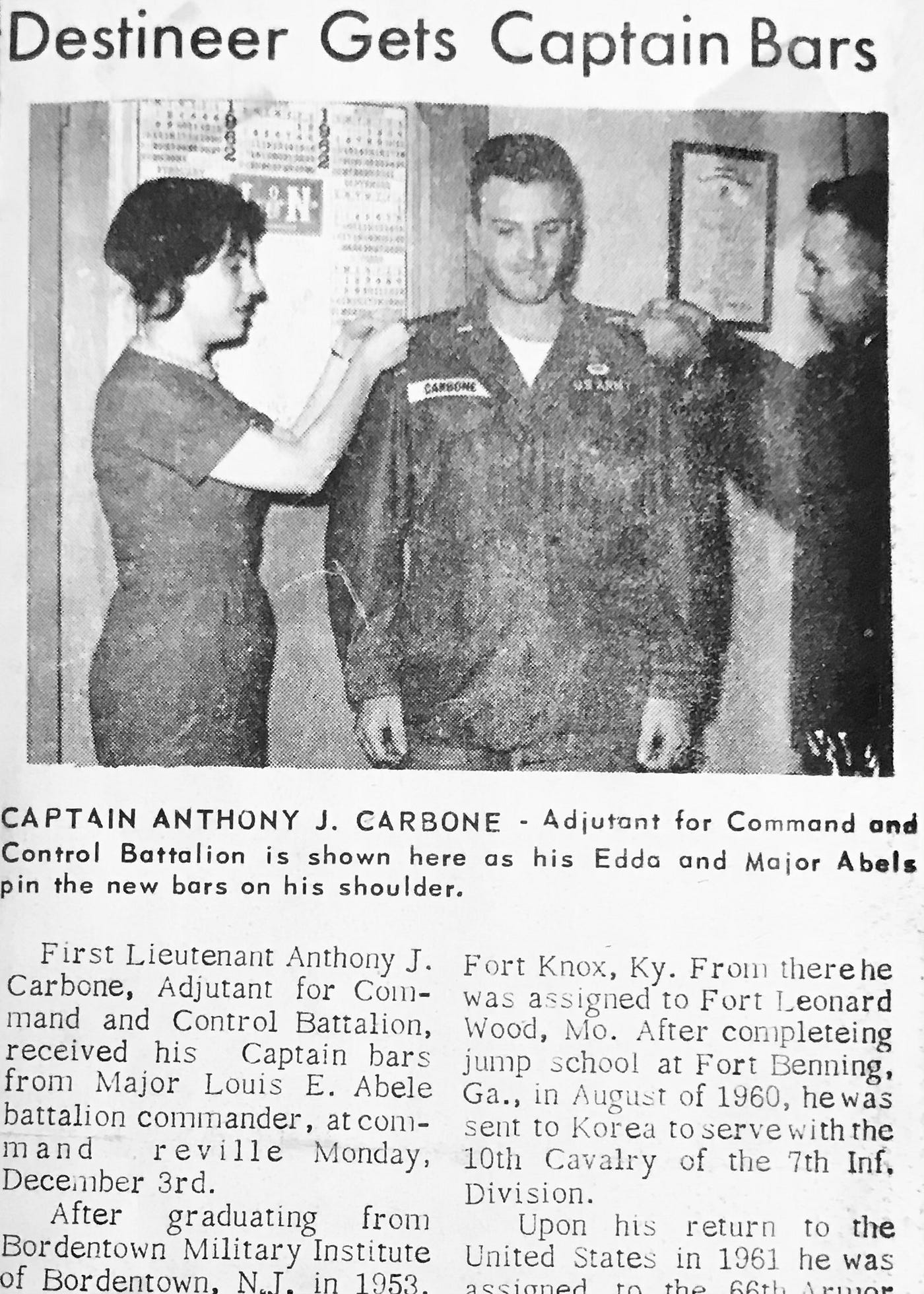

Dad Gets Promoted to Captain

My father was promoted to the rank of Captain on my third birthday. This was while serving as the Adjutant for the Command & Control Battalion of the 101st Airborne Division.

Father Gets Orders for Fort Benning, Georgia

In 1963, was father received orders sending him back to the U.S. Army Infantry School and Center at Fort Benning, Georgia to attend the Infantry Officer Advance Course. This was considered an honor and special assignment for an Armor officer.

President & Mrs. Kennedy Travel to Texas and the World Changed

And then came Friday, November 22, 1963. I was not yet four years old, but I remember that day with the kind of clarity that defies age. It was the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. The world stopped.

The Moment of the Assassination of the President in Dealy Plaza

Walter Cronkite Officially Announces the Death of President Kennedy on Live Television

Our home fell into an eerie silence. My parents sat motionless, tears in their eyes, staring at the black-and-white television. I didn’t fully understand what had happened, but I knew it was something terrible. Even as a young boy, I already knew about the Secret Service. I also knew the President was the most powerful man in America. And now, even he could be shot in broad daylight. That single realization shattered something inside me.

I suddenly understood the world wasn’t safe, and I was afraid that my father would now have to go to war. I already knew — instinctively — that war was a bad and dangerous place.

That weekend was unlike any other. We were all home, transfixed by the television as we watched President Johnson get sworn in on Air Force One and saw Kennedy’s casket return to Washington.

Lee Harvey Oswald is Assassinated on Live Television

I heard the panicked interviews of Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas — and then, we watched in disbelief as Oswald was shot and killed by Jack Ruby live on TV just two days later.

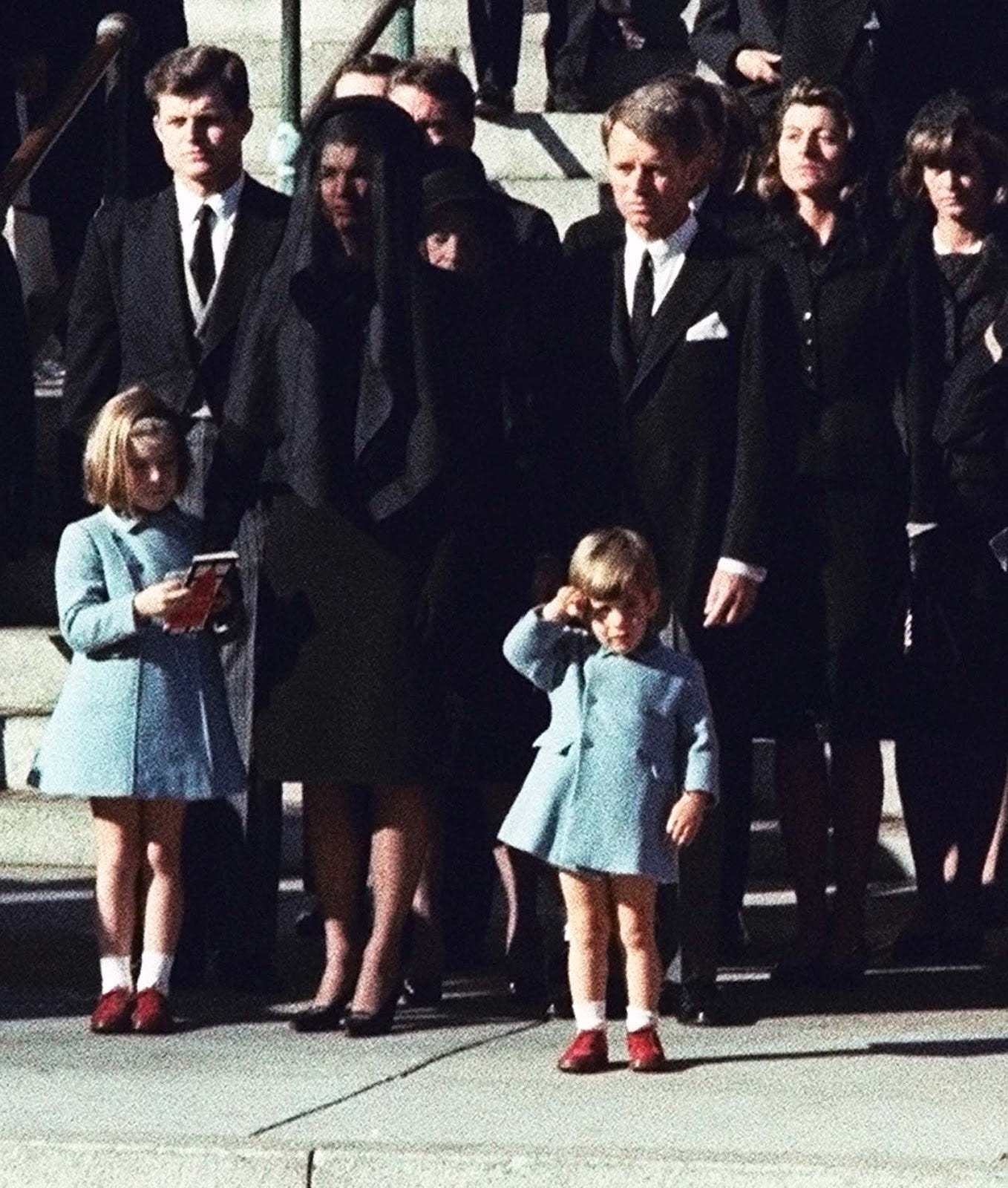

The Late President’s Funeral Procession

And then came the long, beautiful, sorrow-filled funeral procession. I still see John-John’s heartbreaking salute. The Old Guard soldiers. The late President’s casket on the caisson. Black Jack, the riderless horse. The muffled drums. The silence of millions.

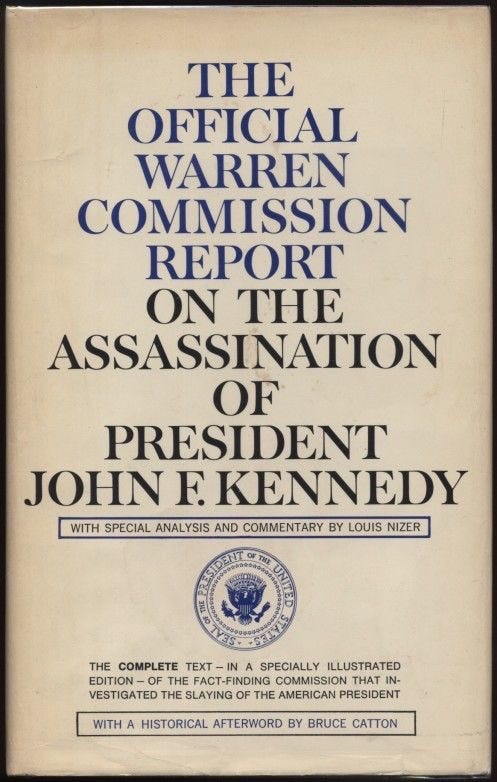

The Infamous Warren Commission Report

The trauma of that moment stayed with me. It gave me nightmares for years. It also ignited a lifelong obsession with understanding what really happened. The very first nonfiction book I ever read was The President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. Even as a child, I could tell it wasn’t right. The Warren Commission’s report was filled with holes — chapters openly admitted that facts and testimony had been disregarded simply because they didn’t fit the predetermined outcome.

I didn’t buy it. I was one of the earliest skeptics I knew. Sixty years later, I’m still studying that moment in history. That day in November didn’t just end the Kennedy era. For me, it ended childhood.

Father Receives Orders for Germany

Shortly afterward, my father received new military orders. In early 1964, we packed up once again and prepared to travel to Germany for our first of three tours to Europe.

But I left a part of my innocence behind in America — along with the memory of a young president whose life and death taught me that truth is not always what it appears or what we’re told.