Chapter 4: Our First Tour in Germany: Fulda and Heidelberg

- Anthony Carbone

- Jul 22, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2025

BELIEVE NOTHING YOU HEAR, AND ONLY HALF OF WHAT YOU SEE — A Memoir of Service, Shame, and the Search for Truth

Dad Gets Orders for Fulda, Germany

In 1964, during the height of the Cold War, my father received deployment orders to Fulda, West Germany. The Berlin Wall had only recently gone up, and global tensions were at a boil. It was a serious time, and the assignment my father received reflected that gravity.

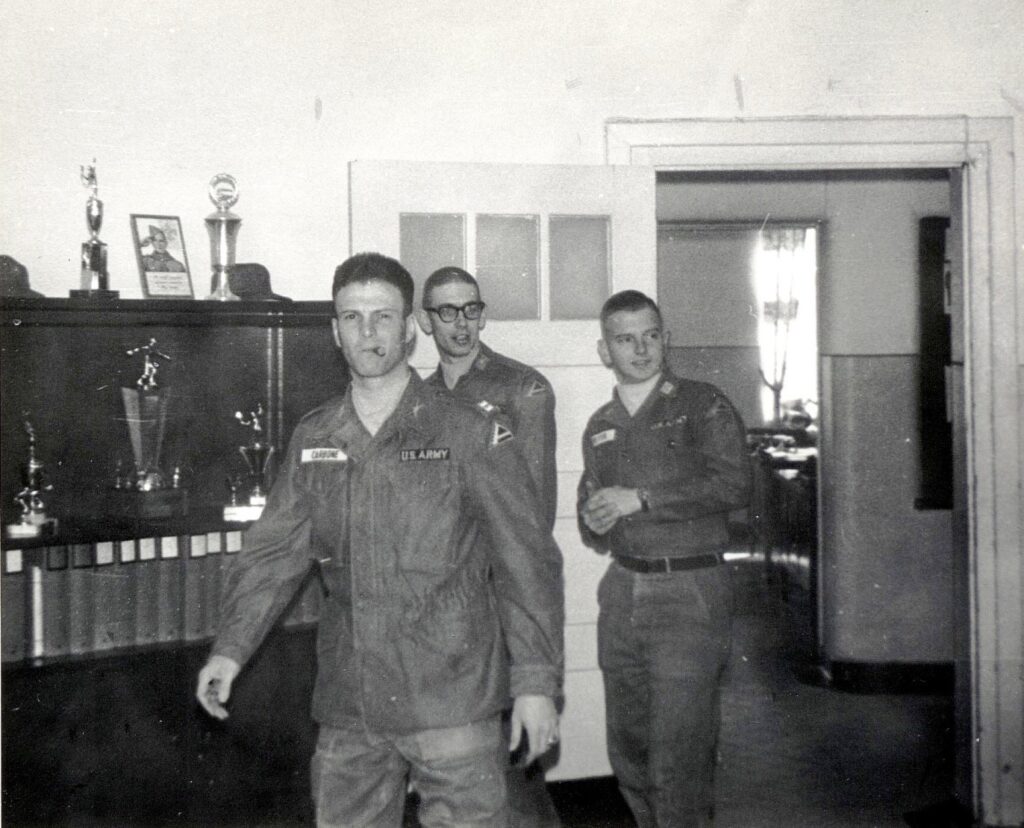

Command of C Troop, 14th Armored Cavalry

Dad was given command of C “Charlie” Troop, 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment, in Fulda, Germany — stationed at one of the most sensitive flashpoints between NATO and the Warsaw Pact.

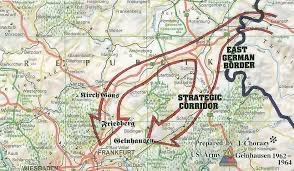

The Fulda Gap

Known as the “Charging Charlies“, C-Troop (and the rest of the 14th Cavalry) was responsible for guarding the infamous Fulda Gap, the strategic corridor military planners believed the Soviets would use to launch a massive armored invasion into Western Europe.

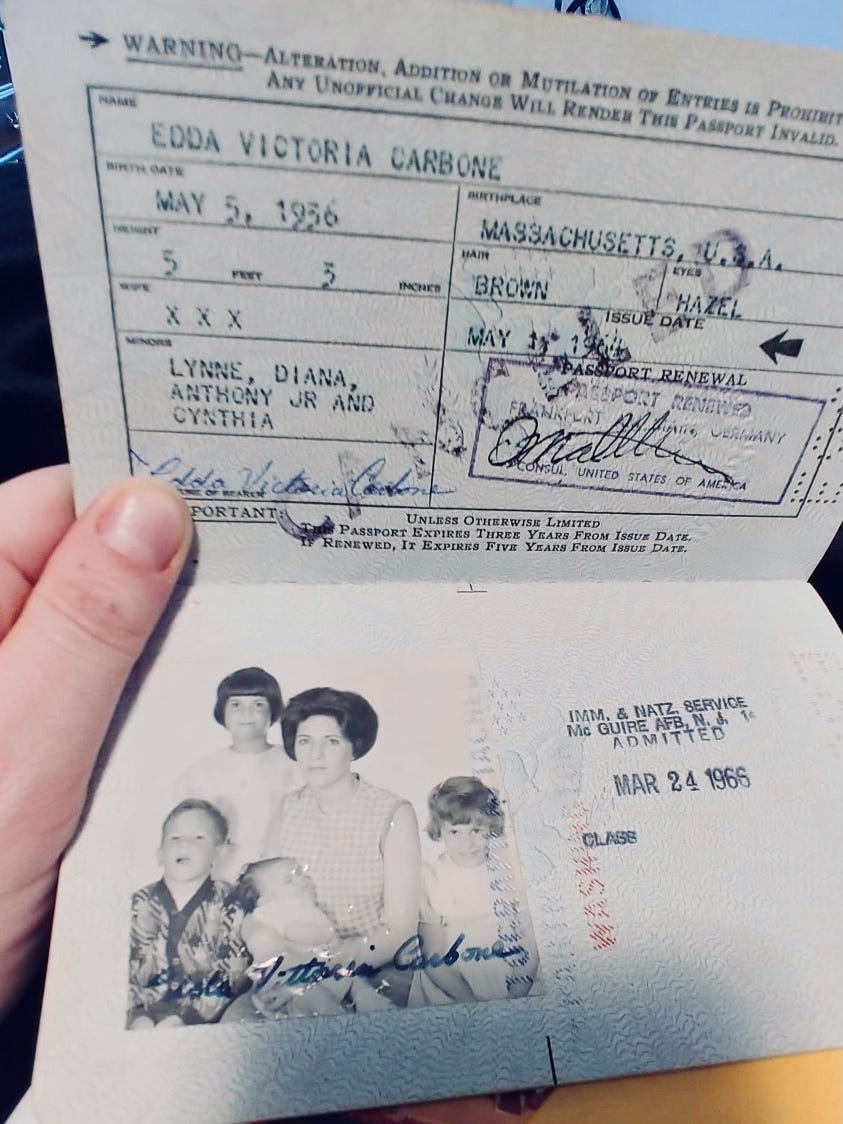

Family Prepares for a Transatlantic Transfer

My father deployed ahead of us to report for duty and secure housing, while the rest of us — my mother, my three sisters, and I — prepared for the long move overseas. The process of uprooting our lives for Germany was as complex as it was memorable. Every item we owned had to be sorted into four categories: (1) Hold Baggage — essentials that traveled by air; (2) Household Goods — the bulk of our possessions, shipped by slow-moving cargo ship; (3) Storage — items too big or unnecessary to bring; and (4) Trash or Give Away — whatever wouldn’t make the cut.

Birth of Sister #3, Cynthia

Just weeks before our departure, on January 29, 1964, my third sister Cynthia was born. Her arrival added both joy and urgency to our preparations. With a newborn in the house, the challenge of organizing an international military move became even more formidable. But as always, my mother handled everything with grace and efficiency — tending to Cynthia’s every need while managing three other young children and the complex logistics of uprooting a household. Cynthia took her very first flight as an infant in her mother’s arms, beginning a life already shaped by service, travel, and family sacrifice.

Though I was very young, that journey remains burned into my memory. We traveled to McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey, where we boarded a sleek four-propeller Douglas C-118 Liftmaster aircraft operated by the Military Air Transport Service (MATS)— packed mostly with uniformed GIs. We were one of the few military families on board. My mother, ever composed and elegant, wore a pencil skirt and sweater, her trademark pearl necklace resting neatly at her collar as she carried my baby sister Cynthia in her arms. She handled the journey with grace, even while managing four children. I remember GIs stepping in to help — each of us was being held or entertained by a soldier at one point. It was a shared moment of kindness and connection in a time of great upheaval.

Family Flies to Germany — Headed to Fulda

The flight took us from McGuire to Gander, Newfoundland, then across the Atlantic to Shannon, Ireland, and finally to Rhein Main Air Force Base in West Germany. It took 16 to 18 hours, and when we landed, we were met by my father and our “sponsors” — an Army family assigned to help us transition into German life.

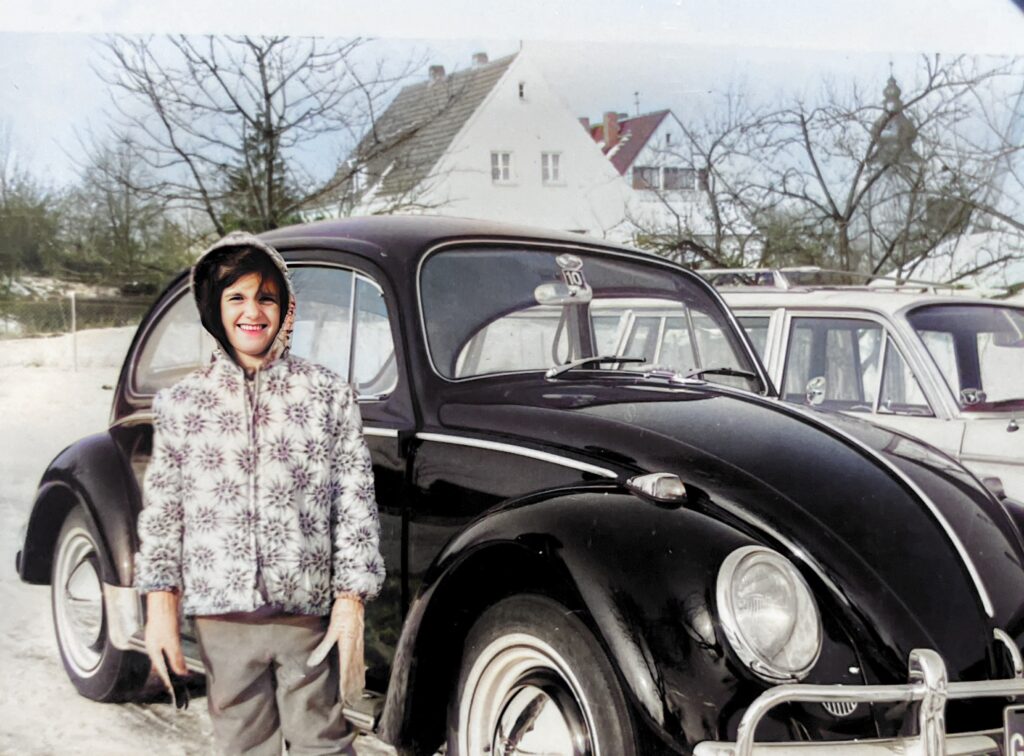

We live on a farm on the Germany “Economy”

At that time, there were no on-post quarters available for us in Fulda, so we rented a home “on the economy,” Army-speak for off-base living. Our rented house sat on a small German farm, nestled in the hills above a Catholic school that I attended for kindergarten alongside my sisters Lynne and Diana. The nuns who taught us wore full habits and ran a tight ship. I remember the heavy wooden Brio toys we played with, the scent of peppermint tea served before naps, and the solemn atmosphere of strict German discipline.

Our landlord’s daughter, Effie, was a teenage girl with long blonde braids who lived downstairs and was mainly Lynne’s friend. Our babysitter was Marlena lived up the street from us. She spoke just enough English to make herself understood and was endlessly patient with us.

My favorite sights, sounds and smells of Germany

Some of my most vivid childhood memories are rooted in that farm — the air thick with the scent of wildflowers, blossoming trees, and the unforgettable smell of “honeywagons,” large wooden barrels filled with manure used to fertilize the fields. Coal was still the primary source of heat, and the smoky, sulfur-rich air had a strange health to it — earthy and alive, part of the rural rhythm of Fulda. Another sensory thread woven deeply into those memories is the sound of church bells. They marked the hours with gentle regularity, rang out at midday for the Angelus, and on Sundays, filled the valley almost nonstop from dawn to dusk. Even now, the tolling of bells brings me instantly back to Germany — awakening a sense of calm, nostalgia, and rootedness that no other sound quite can.

Dad Commands F Troop, 14th Armored Cavalry on Soviet Border

I don’t believe we owned a car at the time, so my father was picked up daily by his jeep driver to report to the regiment. It didn’t matter to me that we didn’t have a car because we loved living on the German farm. I was utterly captivated by the world we had entered. Even then, as a small boy, I had already made up my mind: I wanted to be a cavalry officer just like my father. I watched him closely, studying how he wore his uniform, how soldiers saluted him, how he led. To me, he was a hero, and I never questioned that I would follow in his footsteps someday.

We move on post into government quarters on Rose Barracks

Eventually, our family received government quarters. We moved into a tall, gray three-story apartment building that housed twelve Army families. The fourth floor had maid’s quarters built by the Nazis decades earlier. It wa, a haunting reminder of Germany’s past tucked above American military life. From my bedroom window, I could see the military airfield nearby. At night, as I lay in bed reading comic books under the covers. The rotating airfield beacon would cast alternating flashes of green and two white lights into my room. That rhythm of light, sweeping silently across my walls and pages, felt like a lullaby — strange, comforting, and unforgettable.

Life on a cavalry post thrilled me. My father gave me occasional tours of the motor pool, the barracks, and the tanks. I couldn’t get enough. The Military Police (actually Unit Police–UPs) at the gate would sometimes let me stand next to them, waving in vehicles and offering salutes. The whole environment was electric to a young boy with big dreams.

The Grim Reality of Guarding the Soviet Border

It wasn’t all parades and salutes for the 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment. Their mission was deadly serious. The regiment’s men actively guarded the infamous Fulda Gap, stationed at the spear’s tip.

Military planners expected that if the Soviet Union ever unleashed its armored divisions into Western Europe, the main thrust of their invasion would come roaring through this very corridor.

To the untrained eye, the countryside around Fulda was idyllic. Rolling hills, fertile farmland, and quiet villages created the picture of peace. The landscape gave no hint of the threat that loomed just across the line. However, the soldiers of the 14th Armored Cavalry knew better. They patrolled the NATO border daily, often within meters of East German and Soviet forces. From their observation posts, they could see the enemy through field glasses—watching them as intently as they were being watched in return.

Need for Tank Gunnery Proficiency

For these troopers, there was no illusion of safety. Tank gunnery, live-fire ranges, and field maneuvers weren’t training games—they were rehearsals for survival. Every round fired, every drill practiced, was preparation for the day the balloon might go up, when the border could erupt in fire and steel without warning.

The 14th Cavalry’s unspoken duty was to slow the Soviet juggernaut long enough for NATO reinforcements to mobilize. Everyone knew what that meant: if war broke out, the enemy would overrun the regiment in hours, perhaps even minutes. It was a grim reality, but one they carried out with quiet professionalism. To a boy watching from the safety of Army quarters, the regiment looked like knights in armor. Unfortunately for the men who wore the spurs, it was a mission shadowed by constant danger.

Baby Sister, Pamela, is born in Germany

During this tour, our family grew again. My baby sister Pamela was born on September 11, 1965 at the 97th General Hospital in Frankfurt, Germany. My mother was too far along in her pregnancy to make the long trip home, so Pamela became the only one of us not born at Lawrence Memorial Hospital in Medford, Massachusetts. She even held dual American-German citizenship until she turned eighteen.

Our first deployment to Germany wasn’t just a posting — it was the beginning of my lifelong identification with the Army, with cavalry tradition, and with the kind of honorable service my father embodied. It was the chapter where I began to understand who I was becoming — and who I aspired to be.

Dad Gets Orders for HQ USAREUR in Heidelberg, Germany

As his command in Fulda came to an end, our family received new orders: a transfer to Headquarters, US Army Europe and 7th Army (HQ USAREUR) Heidelberg. This meant a new home for our family — one unlike any we had experienced before. We relocated to an American military housing area called Patrick Henry Village (PHV), located just on the outskirts of Heidelberg.

Our Family Moves Into Post Housing — Patrick Henry Village

PHV was more than just a place to live; it was a self-contained American suburb transplanted into the heart of Germany. During the Cold War, it became one of the largest military family housing areas in Europe, with over 16,000 Americans living in approximately 1,500 apartment buildings. Every building looked exactly the same — white-painted concrete blocks with terra cotta roof tiles, lined up in precise rows. Each building contained three stairwells, with 18 apartments stacked over three floors.

The fourth floor usually housed maids’ quarters or temporary billeting units. From the outside, there were no distinguishing features.

That fact became a nightmare on my very first day of school when I got hopelessly lost trying to find my way back home. Every building looked the same, and the playgrounds behind them all were full of noisy children. To this day, I have no idea how my mother managed to find me in that uniform maze of concrete, stairwells, and unfamiliar faces — but she did.

Aerial View of PHV Shows Size and Similarity of Post Housing

Playing freely on Post Housing Area in Patrick Henry Village

Despite that early trauma, I quickly adapted and grew to love life in Patrick Henry Village. Behind each building was a small playground, usually occupied by a noisy cluster of children from different corners of the country, brought together by the rhythm of Army life. After school and on weekends, those playgrounds became our kingdom. We ran wild until the familiar rituals of military tradition called us back to order.

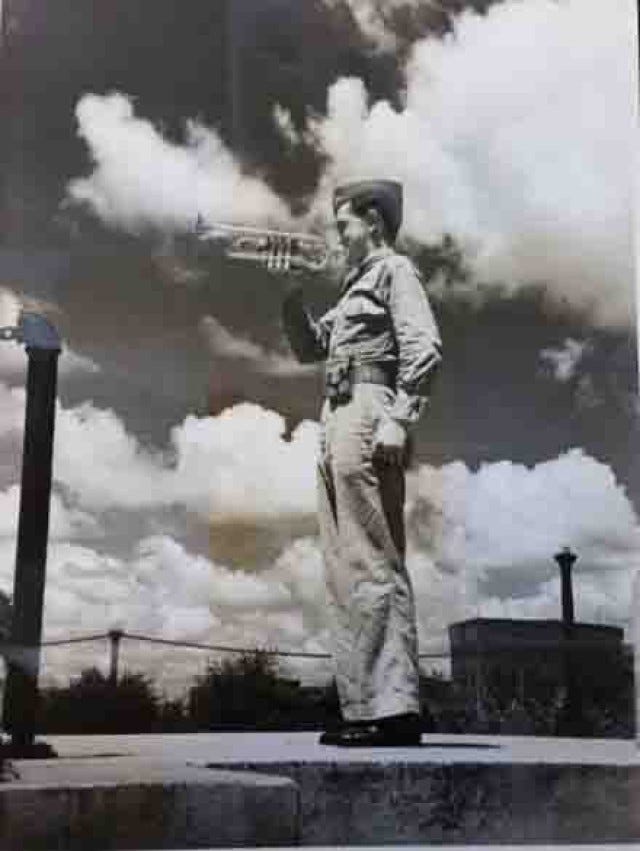

Military Bugle Calls

Every evening at exactly 1700 hours, a cannon blast echoed across the post, followed by the bugler’s mournful notes of “Retreat” and “To The Color.” At that moment, everything on base stopped. Cars pulled to the side of the road. Soldiers stepped out and faced the flag. Children froze in mid-play, instinctively turning toward the post colors. Everyone stood silently until the last note faded. That simple act — performed every day — instilled in me a deep and abiding sense of patriotism. Even today, the memory of it gives me goosebumps.

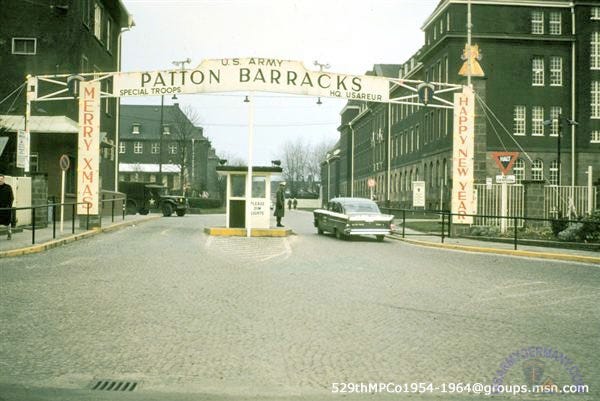

HQ USAREUR at Patton Barracks in Heidelberg

My father’s duty station was at Patton Barracks, which housed the Headquarters of United States Army Europe (USAREUR) and the 7th Army. As a boy, I didn’t fully grasp the weight of those names or the significance of the command my father now served. But I understood that he wore his uniform with pride, and that our family’s life revolved around a larger mission. We belonged to something big.

We Enjoy Off-Post Visits to Altstadt Heidelberg

Though Patrick Henry Village was distinctly American, we were just a short ride away from one of the most beautiful cities in all of Europe — Heidelberg. Nestled on the banks of the Neckar River, Heidelberg is a city of old-world charm and deep historical roots. Dating back to the time of the Celts and Romans, it is best known for its stunning Schloss Heidelberg — a romantic, partially ruined castle perched on a hill overlooking the river and the old city.

Altstadt Heidelberg

My favorite part of Heidelberg was the Altstadt — Old Heidelberg — located along the river beneath the castle. Its cobblestone streets wound past the Heiliggeistkirche (the Church of the Holy Ghost) and over the beautiful Alte Brücke, the Old Bridge. We spent many Sundays wandering those streets, exploring castle ruins and soaking in the beauty of this ancient town. On most Sundays, our family ritual began with mass at the post chapel, where I served as an altar boy. Afterward, we’d drive to the Officer’s Club for Sunday brunch — a tradition that blended sacred and social rhythms into a weekly ceremony of our own.

Auntie Norma Stays with us Again

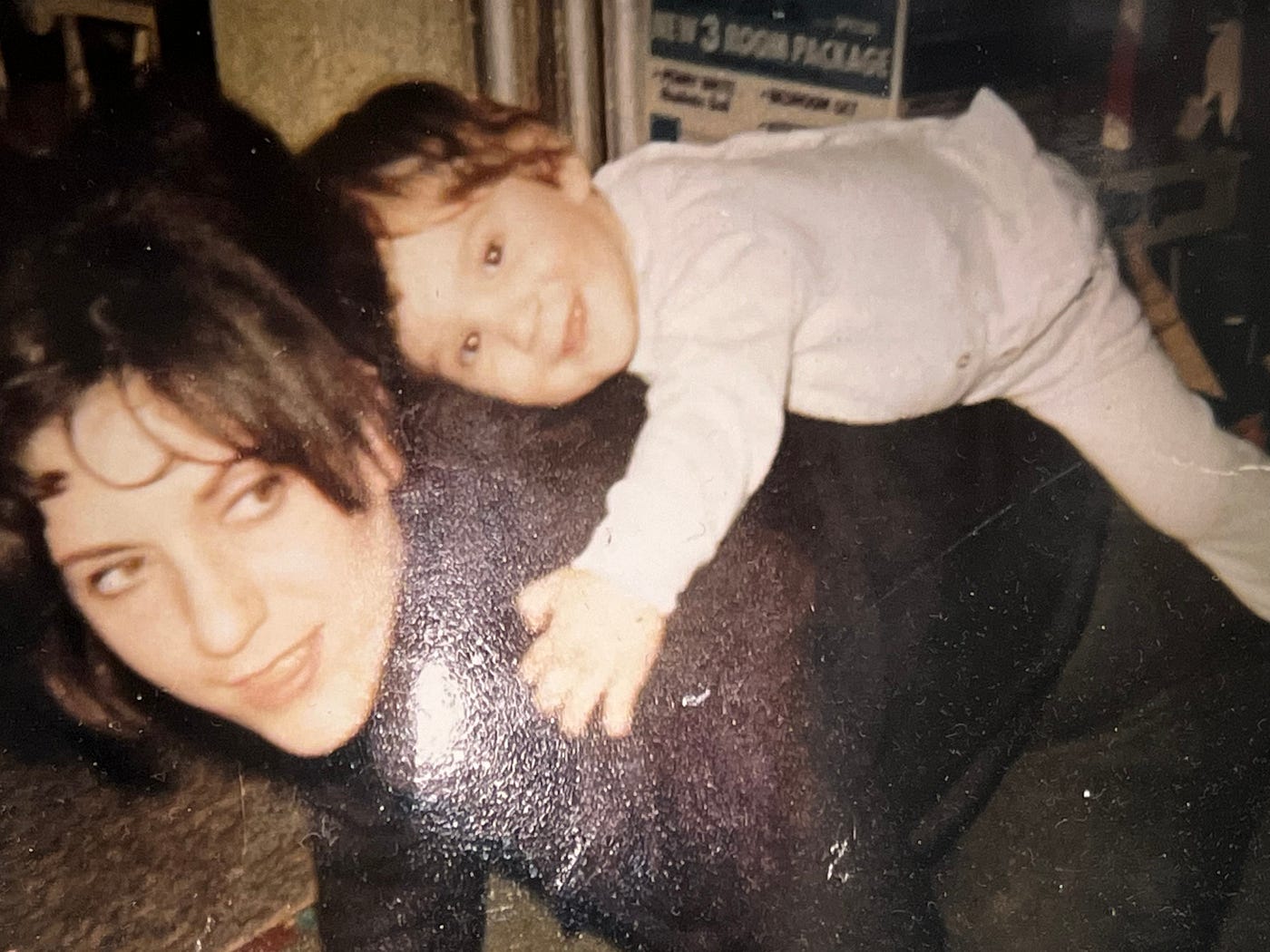

During this period, one of the most beloved figures in our family life came to stay with us — my mother’s younger sister, Norma Pietrantoni. Auntie Norma had always been a special presence in our lives, visiting us at every post we were assigned to, often stepping in as a second mother or nanny. In the 1960s, she worked as the personal secretary to the President of Harvard University. But when her boss took a sabbatical, Auntie Norma made a bold decision: she packed her suitcase and lived with us in both Fulda and later in Heidelberg for several months.

At a time when it was rare for single women to travel alone, Auntie Norma became a fearless explorer. While helping my mother care for my baby sisters, she also toured Europe — sometimes joining military-sponsored trips with soldiers, and other times venturing out entirely on her own. She was an avid photographer and the person behind most of the 16mm movie reels that captured our childhood in Germany. Thanks to Auntie Norma, so many of our memories from that magical time were not only lived but beautifully preserved.

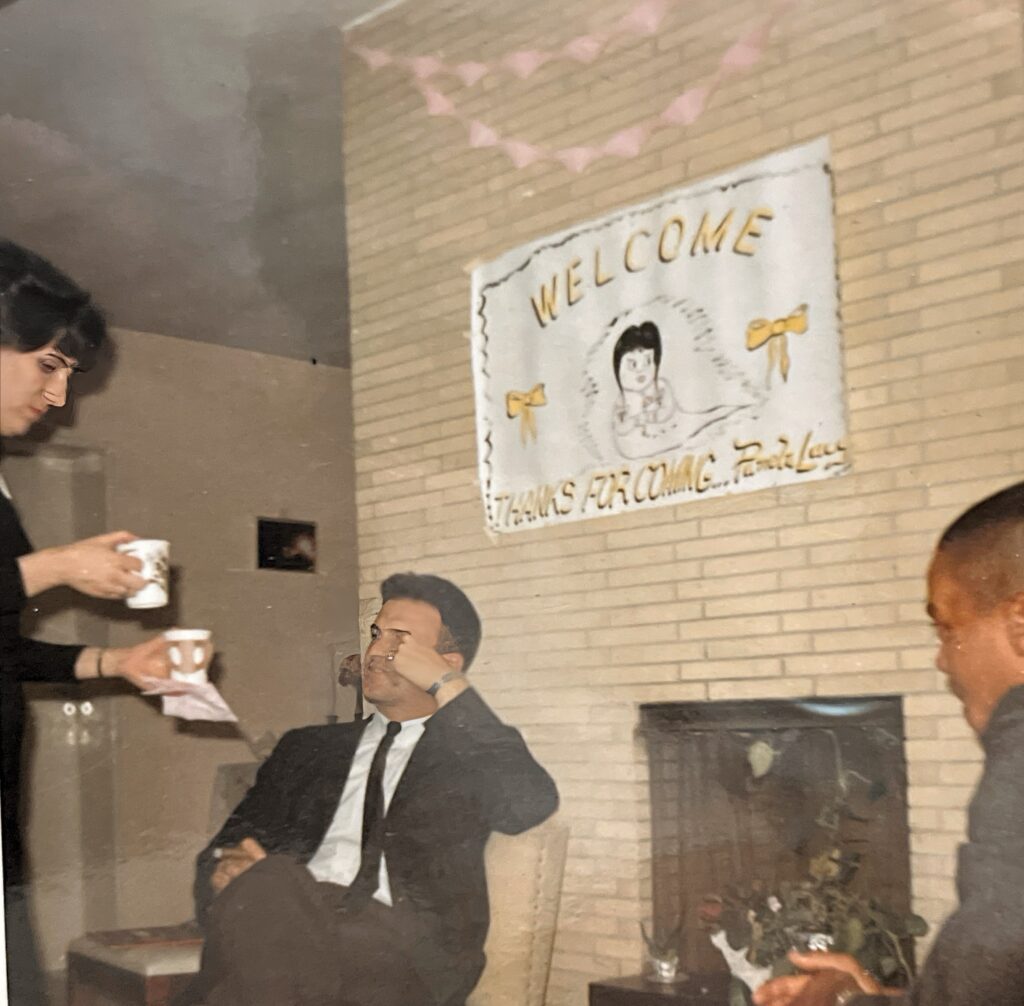

Lynne’s Birthday in Heidelberg

Heidelberg became more than just a city to me. It was a place of magic and mystery, history and reverence. The contrast between the crisp, ordered life of Patrick Henry Village and the timeless elegance of Heidelberg shaped my understanding of the world. One was duty, the other was beauty — and I was lucky enough to be raised with both.