Chapter 6: A Year in Vermont as Dad Returns to His Alma Mater

- Anthony Carbone

- Jul 22, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 15, 2025

BELIEVE NOTHING YOU HEAR, AND ONLY HALF OF WHAT YOU SEE — A Memoir of Service, Shame, and the Search for Truth

Return to Norwich University

After completing his tour of duty in Korea, my father received new orders that must have filled him with pride: he was to return to his alma mater, Norwich University — the Military College of Vermont — as an Assistant Professor of Military Science. For him, it was more than just a job; it was a return to the place that had shaped him as a young man and launched his military career. For our family, it became a unique and vivid chapter — one filled with snowy landscapes, small-town charm, and a few lessons we never forgot.

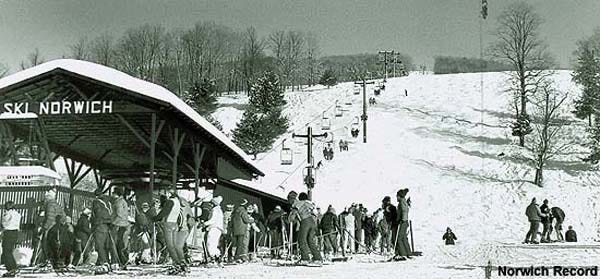

We move to off-campus house in Northfield, Vermont

We moved into a modest white ranch house at the foot of the Norwich ski slope, within easy walking distance of the campus. The house was small but cozy, and the setting was pure Vermont. Behind us sat Trombley’s greenhouse, where we could buy ears of corn and other fresh vegetables. It was one of those places where the seasons announced themselves through what was available at the roadside stand.

Lynne goes to 5th Grade in One-Room Schoolhouse

My oldest sister, Lynne, went to fifth grade in a tiny white, one-room schoolhouse located in Rabbit Hollow. The school was so small that it only served fifth graders.

Diana and I attend 4th & 3rd Grade Together

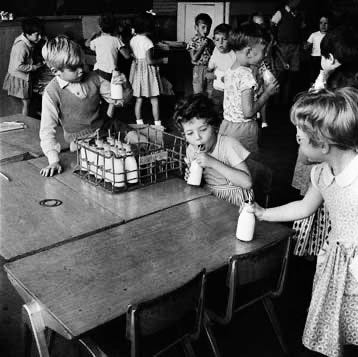

Meanwhile, Diana and I were enrolled in a two-story gray schoolhouse in Northfield that taught only third and fourth grades. She was in fourth, I was in third — and I loved knowing she was just a floor away. We rode the bus together each morning and afternoon, and often shared lunch in the cafeteria tucked down in the basement.

My favorite school cafeteria

That basement cafeteria remains one of my warmest memories — especially on bitter Vermont winter days. The meals were like no other school lunches I’ve ever had. A typical menu might include a warm biscuit smothered in Chicken à la King, served alongside milk that came in small glass bottles sealed with silver foil tops. At least once a day, someone would drop a bottle, and it would shatter spectacularly on the floor. The room would erupt into clapping and cheers, as if we had just witnessed a performance.

Cold, fresh milk in tiny glass bottles

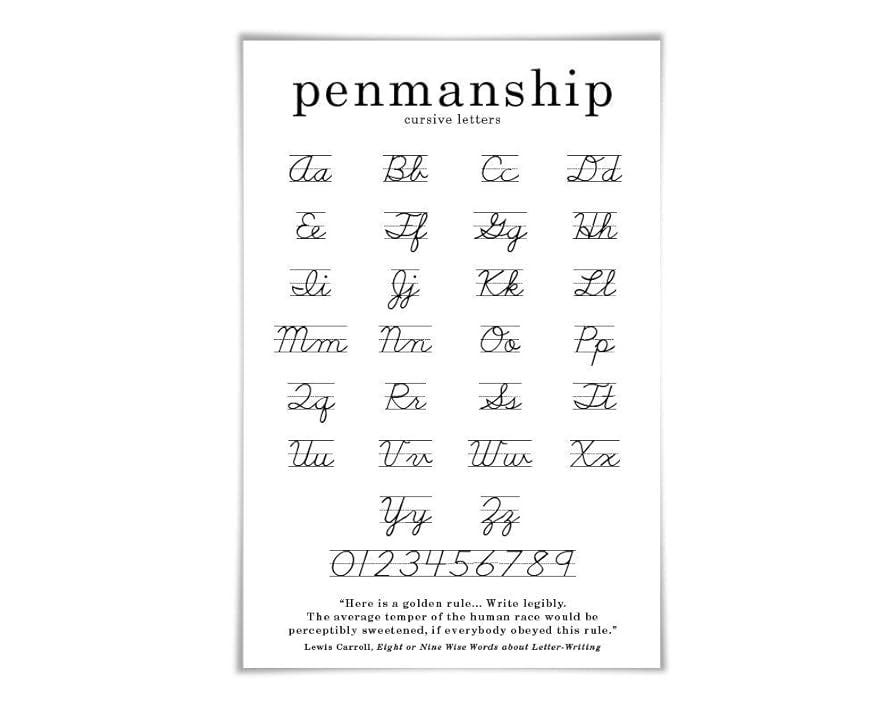

Missed out on learning cursive penmanship

School life had its challenges, though. In Vermont, students were taught cursive writing with ink pens in the second grade. But I had just come from the German school system, where cursive wasn’t introduced until third grade. My new teacher seemed annoyed that I hadn’t learned it yet, and I remember feeling confused and even a little ashamed. It struck me as strange — even as an eight-year-old — that in a town with a military college, someone wouldn’t expect a student from out of state, or even another country. Eventually, my teacher allowed me to keep printing with a pencil, and I wouldn’t truly learn cursive until years later, when my college girlfriend Marianne patiently taught me proper penmanship. To this day, I still write in clear block letters and rarely use cursive.

While we were adjusting to Vermont life, my father was thriving. As the Assistant Professor of Military Science (PMS), he helped lead the Army ROTC program, teaching courses in close-order drill, map reading, and land navigation. I know he took real pride in shaping young cadets on the same campus where he had once marched across the quad himself. It must have felt like coming full circle.

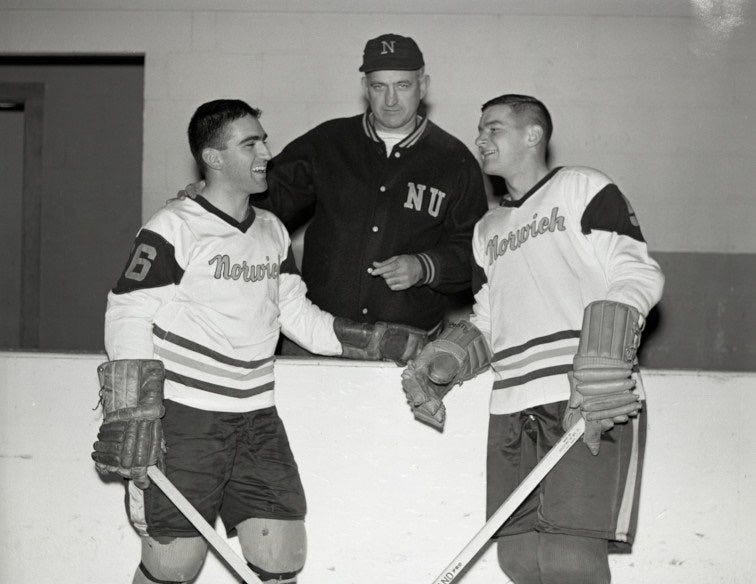

Winter and Hockey in Vermont

As you might expect, winters in Vermont were long, dark, and cold — but the locals seemed to thrive on it. Skiing and hockey weren’t just hobbies — they were part of the culture. Hoping I might assimilate, my father signed me up for hockey lessons offered by the Norwich University hockey coach. It was his good friend, Coach John Norris. I gave it my best, but most of the kids had been skating since they could walk. On the other hand, I was stumbling around in skates that felt at least two sizes too small. I spent more time falling than skating, and one hard fall even chipped my bottom front teeth. That was pretty much the beginning and end of my hockey career.

Northfield Townies

Northfield was a tiny town — just over 3,400 residents in 1960. By 1967, Norwich had about 1,200 cadets, meaning they made up nearly a quarter of the town’s population. But despite that, there was always a strange tension between the college and the townspeople. For whatever reason, the locals didn’t seem particularly fond of the institution that helped sustain their town. The only time that changed was during hockey season — if the Norwich Cadets were winning, the townsfolk would turn out to cheer. Otherwise, the university and the town existed on mostly separate tracks.

Close to the Pietrantonis in Medford

One of the real blessings of that year in Vermont was our proximity to family. Northfield is less than three hours north of Boston, which meant we were finally living close to my mother’s side of the family in Medford. We visited my grandparents’ house often, and my aunts would come up to Vermont when they could. After years of being stationed far from home, it was special to have holidays, birthdays, or even just weekend visits that didn’t require a cross-country drive or plane ride. That closeness was a quiet comfort that made the cold winters feel warmer.

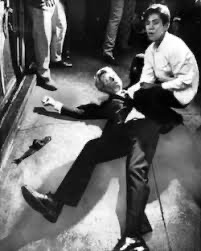

Assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy (June 6, 1968)

It was the morning of June 6, 1968, and my mother had sent me over to Trombley’s Greenhouse to pick up some milk and eggs. The day was bright and beautiful, and I remember stopping in a field along the way to admire a robin’s nest with four perfect blue eggs inside. That simple sight filled me with joy. But when I returned home, the mood was completely different. I could sense immediately that something was wrong. My mother told me that Senator Robert Kennedy had been shot by an assassin. I was still too young to fully understand the concepts of evil and murder, but I knew it was something terrible.

Only a few years earlier, I had sat in front of the television as a very small boy when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Now, it was his younger brother. Just eight weeks earlier, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. had also been assassinated. As a young boy, I struggled to process it all — the war in Vietnam that I only partly understood, and these assassinations of leaders I heard my parents speak about with respect and admiration. It felt like the world was unraveling. I remember being deeply confused, wondering why so many good men were being taken away, and why violence seemed to surround everything I was trying to make sense of.

Time to Move Again

Our year in Vermont was brief, but it stands out in memory as something rare and quietly golden. There was a steadiness to life that year — a rhythm built on snow, school buses, cafeteria clatter, and my father’s cadets drilling in neat formation. It was a pause between larger, louder chapters. And though we didn’t know it at the time, those moments would stay with us longer than many others.