Chapter 7: Command & General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth

- Anthony Carbone

- Jul 22, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2025

BELIEVE NOTHING YOU HEAR, AND ONLY HALF OF WHAT YOU SEE — A Memoir of Service, Shame, and the Search for Truth

Return to the Command & General Staff College as a Tactical Instructor

After returning from Vietnam, the Army sent my father to the Command and General Staff College (CGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. This wasn’t just another stop on the military carousel — it was a pivotal milestone in his ascending career. Officers who were selected early for CGSC earned a mark of distinction.It signaled that the Army saw him not only as a skilled officer but as a leader with long-term potential.

This History of Command & General Staff College

The United States Command and General Staff College is one of the crown jewels of military education. Established in 1881 by General William Tecumseh Sherman as the School of Application for Infantry and Cavalry, it was designed to train officers in the complexities of tactics, operations, and command. By 1907 it had become the School of the Line, and eventually evolved into what is now CGSC. Its mission remains timeless: to educate and develop agile, adaptive leaders who can operate in joint, interagency, and multinational environments — and to advance the art and science of the profession of arms.

Famous Alumni of Command & General Staff College

My father knew that the college had shaped some of America’s greatest military minds. Its alumni list reads like a hall of fame: Eisenhower, MacArthur, Marshall, Patton, Bradley, Westmoreland, and later, Colin Powell and Norman Schwarzkopf. To follow in their footsteps — even to walk the same halls — was both humbling and inspiring.

Family Lives Off-Post in Redwood Gardens in Kansas City

Since on-post housing was limited and claimed quickly, our family settled down in a modest townhouse in a small civilian development called Redwood Gardens, located about 35 miles southeast of Fort Leavenworth, in Kansas City, Kansas. Though a few other military families lived there, it lacked the closeness, safety, and camaraderie of post living. For us kids, it was an isolating and sometimes chaotic environment.

Dad sets up basement as Study

Our townhouse was cramped. My father turned a corner of the basement into a makeshift study where he would disappear for hours, immersed in maps, doctrine, and war histories. The workload at CGSC was intense, and the pressure to excel immense.

The bad memories of Kansas City

My own memories of Kansas City during that time are scattered and, for the most part, not especially fond. That year seemed filled with accidents and discomfort. Pamela fell down the basement stairs and had to get stitches on her face. Diana dove into the shallow end of the neighborhood pool and broke her front tooth in half, eventually receiving a dental cap. I got into a fight when I saw a bully beating up a younger kid — jumped in, broke my hand, and spent the rest of the summer in a cast.

Lynne, Diana and I get Confirmed

One of my more cherished memories I have of our time in Kansas City was the day that Lynne, Diana, and I were all confirmed in the Catholic Church — on the same day — by the Archbishop of Kansas City, Bishop Edward Joseph Hunkeler. It was a peaceful and proud moment in an otherwise trying year.

Papa Carbone Dies

The saddest memory I have from our time in Kansas City was the death of my grandfather, Papa Carbone (Anthony Benjamin Carbone). He had just retired and moved to Florida with my grandmother when he suffered a fatal stroke. I remember my father calling me into my bedroom one evening. I could see that he was upset, and at first I worried I had done something wrong. We both sat on my bed, and he said quietly, “I have some bad news. Your grandfather—my father—died today.” I don’t remember another word after that, but what has stayed with me all these years is that my father cried. It was the first time I had ever seen him cry, and in my whole life with him, I would only see him cry once more. My parents quickly flew to Florida for the wake and funeral, while Auntie Norma came to Kansas City to care for us children.

Columbus Park–The Italian Section of Kansas City

On weekends when my father could sneak away from his studies, we would occasionally, we would make a special trip into the Italian section of Kansas City to stock up on authentic cold cuts — thin slices of mortadella, prosciutto, and provolone cheese — all tucked lovingly into crusty loaves of Italian bread.

In 1967, Kansas City’s vibrant tapestry reflected the rich history of its Italian community, especially in the neighborhood then known as the North End. Since the 1860s, Sicilian immigrants actively built a lively, close-knit area—soon renamed Columbus Park—centering it around Holy Rosary Church and filling it with family-owned shops and bustling markets.

This self-sufficient “Little Italy” offered more than just delicious food — it was a place where tradition, language, and community thrived. Even as changes like the construction of Interstate 35 began to carve through its heart and displace families, the neighborhood remained a beloved reminder of cultural roots and Sunday flavors that felt like home.

My Badass Father the Soldier

But another memory stands out even more clearly — not for its peace, but for its intensity. Just a few doors down from our townhouse lived a parentless family of unruly boys who had clearly slipped through the cracks. They had long, unkempt hair — a growing trend in the late 1960s — and I remember them smoking on their back steps, jeering at us as we passed. One day, they went too far and scared my mother. That was a mistake.

I’ll never forget the moment my father found out. He calmly called out, “Hey, J.R.! Come with me!” and together we stepped into the backyard and walked down the road toward the rough boys’ unit. My father knocked on the door, and the oldest, cockiest of them answered. My father made it very clear: he didn’t want any of them speaking to his wife or his children again.

The kid smirked and said something along the lines of, “What is it to you?” Without hesitation, my father grabbed the kid by his long hair and — in a move I can only describe as quiet thunder — drew his service Colt 1911 .45 caliber pistol and placed it gently but firmly under the boy’s jaw. His voice was low, measured, deadly calm. “This will be the last time that I warn you.” Then he released the boy, turned to me, and said evenly, “J.R., let’s get back to your mother. And never say a word about this to her.” That day left a mark on me. I had always admired my father, but in that moment, I saw him not only as a real soldier. I had never felt so safe in my life.

History of Fort Leavenworth

Despite all the challenges of civilian housing, my heart always returned to the post of Fort Leavenworth. Some of my fondest memories of that tour stem from my personal fascination with the fort’s history, particularly its deep connections to the Cavalry. I actively explored the legacy of General George Armstrong Custer and his 7th Cavalry, as well as the legendary Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry— the same regiment my father had served with during his tour in Korea. I felt a personal connection to that history, one that ran through the bloodline of my own father.

The Fort Leavenworth Museum

The post was still very much a place of history. Many of the old red brick buildings from cavalry days still stood, preserved like time capsules from another era. I repeatedly visited the Fort Leavenworth museum, eagerly exploring its relics from Custer, the 7th Cavalry, and the 10th Cavalry.

There were artifacts and exhibits tied to President Abraham Lincoln’s visit to the post, which added another layer of reverence. My family often made Sunday day trips to the museum. Those quiet visits — walking through dusty uniforms, sabers, saddles, and faded photographs — lit a spark in me. As a child, I regarded Fort Leavenworth as hallowed ground.

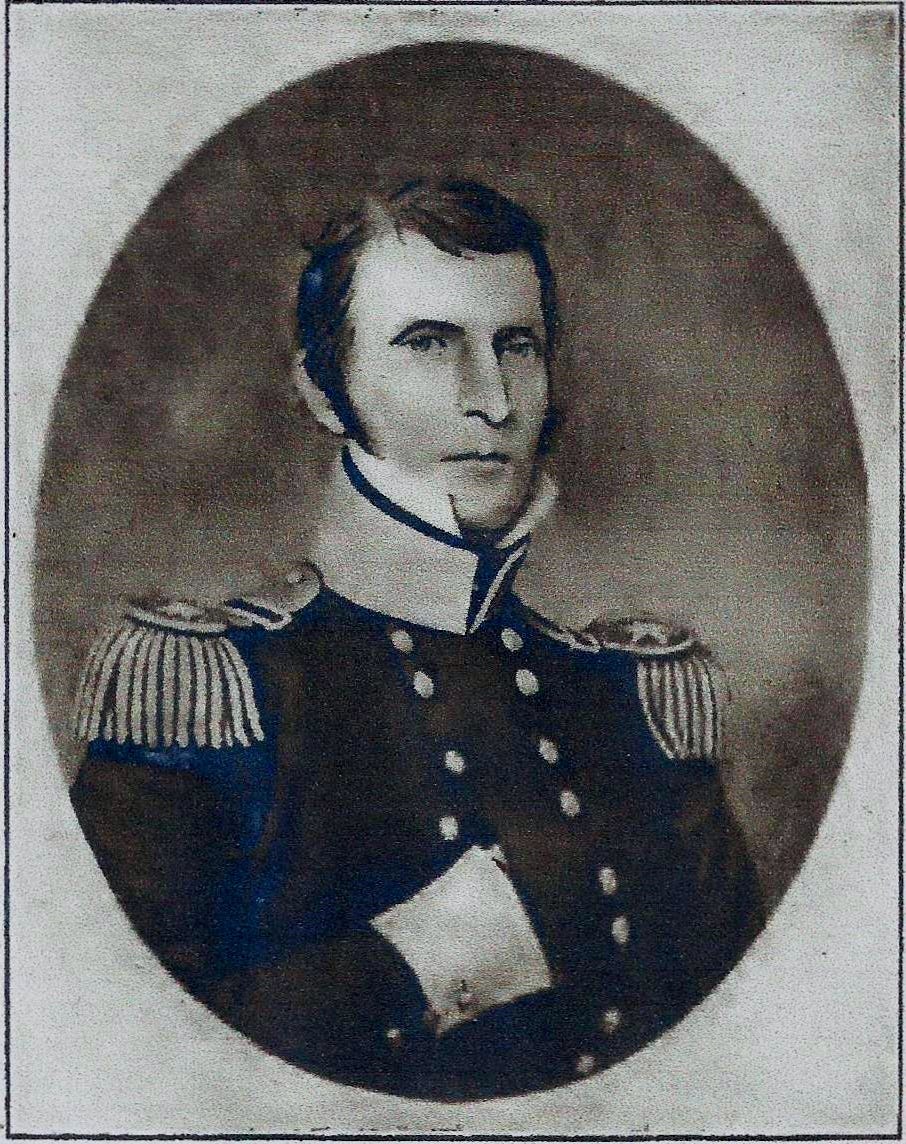

Classic Cavalry-Era Post Housing

The post itself dates back to May 8, 1827, when Colonel Henry Leavenworth established Cantonment Leavenworth along the Missouri River. It became the first permanent settlement in what would eventually become Kansas, and is today the oldest active Army post west of the Mississippi River. Originally serving as a quartermaster depot, arsenal, and garrison to safeguard the fur trade and commerce along the Santa Fe Trail, the post was briefly evacuated in 1829 and occupied by Kickapoo Indians before being re-garrisoned later that same year. On February 8, 1832, it was officially renamed Fort Leavenworth.

Combined Arms Research Library

Over time, the post developed a reputation not just as a military outpost, but as an intellectual center of the Army. It housed the prestigious Combined Arms Research Library (CARL), and it became a place where strategic thought and operational planning were forged and refined.

US Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth

Yet there was another layer to Fort Leavenworth’s identity — its prisons. The United States Disciplinary Barracks (USDB), established in 1875, is the Department of Defense’s only maximum-security military prison.

Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary

Right outside the gates, the Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary, operated by the Department of Justice, stood as a towering reminder of the civilian justice system’s reach.

Famous Resident Convicts

Both institutions had reputations for housing some of the most notorious figures in American criminal and military history — from military murderers and spies to civilian outlaws like George “Machine Gun” Kelly, labor leader Eugene V. Debs, and Robert Stroud, the so-called Birdman of Alcatraz. Their stories seemed to hang in the air like myths. Even as children, we sensed the gravity of their presence, and we were always reminded not to stray too far from home. There was mystery and menace just over the horizon.

Despite the shadow cast by those prisons, Fort Leavenworth stood as a monument to something greater. It was a place of heritage, reflection, and deep military tradition. For my father, the CGSC experience was transformative. It shaped his approach to leadership and helped define the rest of his career. For our family, it was a time of adaptation, growing pains, and strength. And for me, Fort Leavenworth stirred something inside — an early reverence for history, heroism, and the cavalry legacy that connected us all.