Chapter 8: Return to Heidelberg, Our Second Tour of Germany

- Anthony Carbone

- Jul 22, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 15, 2025

BELIEVE NOTHING YOU HEAR, AND ONLY HALF OF WHAT YOU SEE — A Memoir of Service, Shame, and the Search for Truth

Second Tour in Heidelberg, Germany

When I was ten years old, our family once again packed up our lives and headed overseas — this time for our second tour in Germany. My father had received orders assigning him to Headquarters, US Army Europe (USAREUR) and 7th Army, located at Campbell Barracks in Heidelberg. Unlike our earlier tour in the early 1960s, this one brought us back as seasoned travelers. I had already lived in multiple states and countries by then, and yet the thought of returning to Germany filled me with a deep sense of excitement and familiarity.

Father works in the Mushroom

My father’s new assignment placed him in the Plans Department at Headquarters USAREUR, a position that carried immense responsibility. His Top Secret work took place deep in the lower levels of Campbell Barracks headquarters — in a windowless basement complex affectionately nicknamed “The Mushroom.” It was a fitting name for a place that seemed to operate in the dark, both literally and figuratively. There, my father and his fellow officers drafted highly classified contingency war plans in the event of a Soviet invasion through the Fulda Gap — the very terrain he had once patrolled with C Troop, 14th Armored Cavalry.

We Live in Mark Twain Village (MTV) in Heidelberg

Although I didn’t fully understand the gravity of the Cold War at that age, I did understand that my father’s job was important. And we were lucky: his assignment came with stable, convenient housing and a chance to tour Europe. We lived in Mark Twain Village, a government residential community just steps from Campbell Barracks. Our second-floor apartment on Römerstrasse quickly became home.

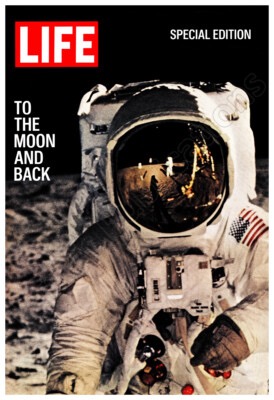

Apollo 11 Moon Landing (July 20, 196)

We had just settled into our new government quarters in Mark Twain Village in Heidelberg when the world seemed to stop for another historic moment. On July 20, 1969, we were glued to our little black-and-white television, watching the Armed Forces Radio & Television Network as the Apollo 11 mission unfolded. The Lunar Module touched down on the moon that evening (around 8PM German time), and I remember the suspense and awe in our household. We even woke up before dawn the next morning to see Neil Armstrong climb down the ladder and take that first step onto the lunar surface. His words — “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” — were broadcast across the globe, and even as a boy in Germany, I understood how extraordinary it was. The mission had launched from Florida on July 16, landed on the moon at 4:17 p.m. EDT on July 20, and Armstrong’s first step came at 10:56 p.m. EDT. By the time the astronauts returned safely to Earth on July 24, the entire world felt changed.

Watching Dad Walk Home from Campbell Barracks

From our living room window, my mother and I would sit together in the early evenings and watch the stream of officers walk home in their uniforms. Even though they all looked the same from a distance — identical green fatigues or Class A uniforms, same gait, same caps — I could always pick out my father by his walk. There was something distinctive and familiar in his stride and the way he tilted his head as though examining the terrain ahead of him, and spotting him from afar gave me a small sense of pride and comfort each day.

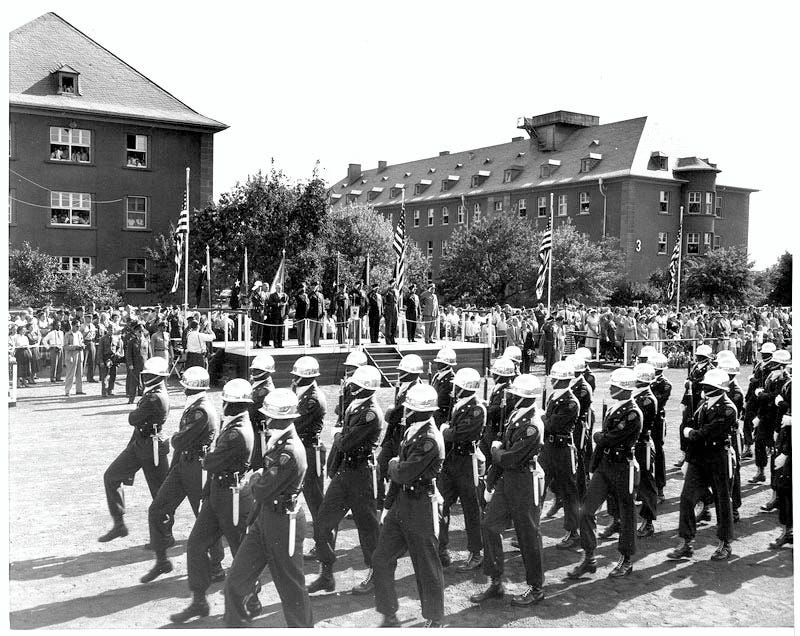

Parades at Campbell Barracks

We were so close to Campbell Barracks that we didn’t just see Army life — we heard it. The bugle calls, the thunderous boom of cannon salutes, and the rousing music of the 7th Army Band became the background soundtrack of our lives. If I had a day off school and it was light outside, I’d run over to Campbell Barracks to watch the soldiers march in “Pass In Review”. Their gleaming boots, synchronized steps, colors and guidons waiving, and perfectly timed salutes made a deep impression on me. It was patriotic, ceremonial, and somehow reassuring.

Life in Mark Twain Village (MTV)

Mark Twain Village was filled with other Army families like ours. The kids played outside until dinner, rode bikes on the broad sidewalks, and gathered for games in the shared courtyards. We attended the American grade school nearby and shopped at the PX and commissary. Even though we were living in a foreign country, our daily life felt predictable and secure — until it didn’t.

Our Car is Used in a Kidnapping

One event pierced that sense of security in a way I’ll never forget. One night, thieves stole our family’s Pontiac station wagon, our trusted vehicle for school runs and weekend drives. Soon after, we discovered that kidnappers used it in the abduction of a young woman.

German and U.S. military police came to our apartment and fingerprinted each of us to help with the investigation of the recovered vehicle. I remember the serious, methodical way they worked, my fingerprints appearing on the identification card, and the sense of something terribly wrong. Later, it was revealed that chloroform had been used during the kidnapping. Our car was returned to us, but it never felt quite the same again. Driving around in it afterward felt strange and unsettling. As a boy, I didn’t yet have the words for trauma, but I knew we had been touched by something dark.

My 5th Grade Teacher Dies of Pneumonia

Another vivid memory from that year is one of personal sorrow. My fifth-grade teacher at Heidelberg American Grade School was only 21 years old. I’ve long since forgotten her name, but not her beauty or kindness. Even at ten, I knew we were lucky to have such a lovely and caring teacher.

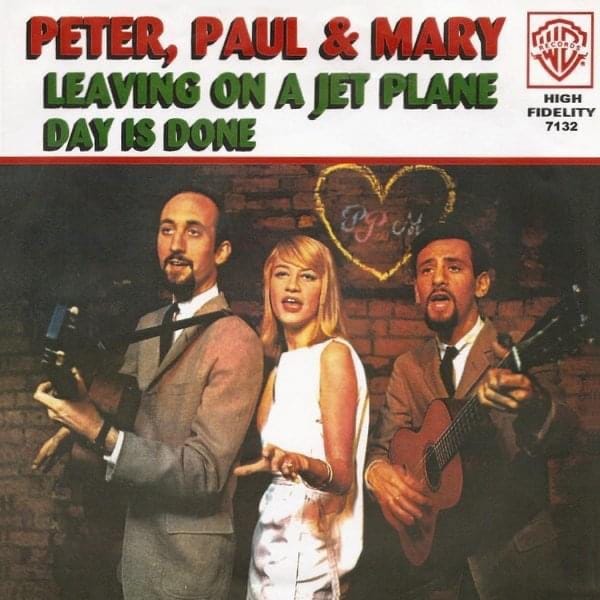

Then one day, we were in the car — my parents in the front, me sitting in the middle between them on the bench seat — and Peter, Paul & Mary’s “Leaving on a Jet Plane” came on the radio. I liked the song already, but suddenly it took on a whole new meaning. My parents turned to me gently and told me that my teacher had died — of pneumonia. I was stunned. “Pneumonia?” I asked. “Isn’t that curable with antibiotics?” They nodded softly but didn’t offer much more. I sat in silence as the song played, numb with disbelief. I don’t remember another thing about fifth grade. To this day, when I hear “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” I’m transported back to that car ride and the overwhelming sadness of losing someone so young.

I learn about suicide

That was not the only moment during our time in Heidelberg that shattered my childhood innocence. I remember another day, driving down Römerstrasse with my parents in that same Pontiac station wagon. I was again sitting between them in the front seat, the hum of the engine and the rhythm of everyday life lulling me into a sense of routine.

Then I heard my father whisper something to my mother. I couldn’t catch it all, but I heard enough: “The captain’s wife… she committed suicide.” My ears perked up. “What’s suicide?” I asked. My parents hesitated, then replied with quiet gravity, “It means she killed herself.” I was stunned. “Why would anyone kill themselves?” I asked again. They explained gently that she had been terribly homesick, living so far from her family, isolated in a foreign country. But I couldn’t understand how loneliness could drive someone to end their life. It seemed unthinkable.

As we continued driving, Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now” came on the radio — “Bows and flows of angel hair…” — and that haunting melody fused itself forever to that moment. I couldn’t make sense of it then, and to be honest, I still struggle with it now. The suicide of that young officer’s wife marked me deeply. From that day on, suicide became something that both baffled and upset me — and it still does.

Nana Carbone visits us in Heidelberg

Despite these dark memories, Heidelberg was also a place of beauty, warmth, and family connection. During this tour, we had two long-time visitors who brought their own special energy to our household. My father’s mother, Nana Carbone, came to stay with us for a while. Our three-bedroom apartment was already tightly packed — my parents had their room, my four sisters shared another, and I had a small bedroom to myself. When we had overnight guests, I gave up my room and moved in with my sisters, sleeping on the floor between their two huge wooden bunkbeds. That simple act became a routine of sorts, and I never minded.

8 of us in a VW Beetle from Heidelberg to Paris

We took Nana sightseeing around Heidelberg and beyond, but I especially remember one spontaneous Saturday morning at the breakfast table. My father asked, “Who wants to go visit Paris?” We all exploded with excitement, raising our hands and pleading to go. He told us to gather our money — every coin and bill we could find, both American and German. We brought him our coins, our Deutschmarks, our pfennigs, and he carefully counted them up and announced that we had just enough.

The funniest part was that we no longer had the station wagon — at the time, we only had a 1960s-era German Volkswagen Beetle. So all eight of us — my father, Nana Carbone, my mother, and the five Carbone kids — crammed into that tiny car, along with our luggage, and drove all the way from Heidelberg to Paris. My father drove, Nana rode up front, and the rest of us — every last one — sat piled in the back, sandwiched together like sardines. It was cramped, absurd, and completely unforgettable.

Auntie Norma Stays with us Again

We also hosted my Auntie Norma that year. She came to stay for an extended visit and, as always, I gave her my bedroom and joined my sisters on the floor. Auntie Norma traveled with us occasionally, but she also took full advantage of Army-sponsored trips for officer wives and soldiers. She explored Europe independently, sometimes with others, often alone, always intrepid with cameras in hand. She was fearless, curious, and full of stories. Her presence added color to our home, and her spirit of adventure made a lasting impression on me. She has always been a part of our nuclear family to me.

I loved Germany

Although everyone in my family lived through three tours in Germany, the timing of this particular tour in my childhood made it the most significant for me. Germany — especially Heidelberg — became an essential part of my identity. Studying the German language began both in school and independently. German history, culture, and geography sparked deep fascination, leading our family to travel throughout the country. Military life, particularly my father’s role in the U.S. Army and the broader structure of NATO forces stationed across Europe, especially captivated me.

Even then, I knew I wanted to follow in my father’s footsteps. I was determined to become an Army officer. And I dreamed of returning to Germany for as many tours as the Army would allow.

Looking back, our second tour in Germany was not just another chapter in our family’s military life — it was the foundation of my emerging sense of self. It was a time when I began to understand the complexity of the world, to absorb culture, history, and tragedy, and to see clearly the path I would one day walk. Heidelberg wasn’t just a post — it was a place where I began to grow up.