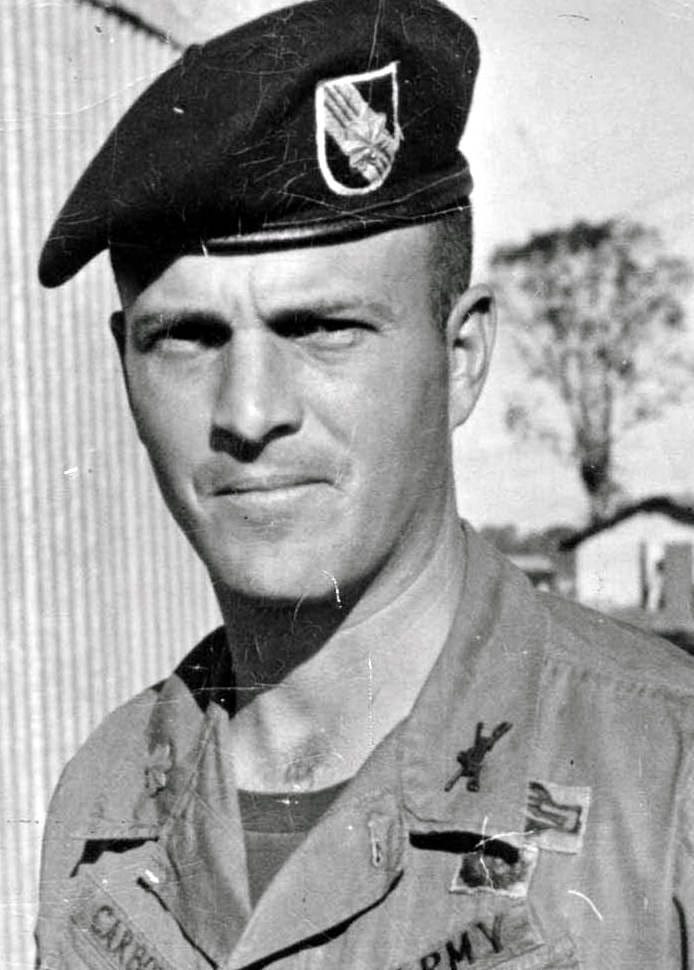

Chapter 9: MACV-SOG: My Father’s Top Secret Mission as a Black Operations Green Beret

- Anthony Carbone

- Jul 22, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Sep 6, 2025

BELIEVE NOTHING YOU HEAR, AND ONLY HALF OF WHAT YOU SEE — A Memoir of Service, Shame, and the Search for Truth

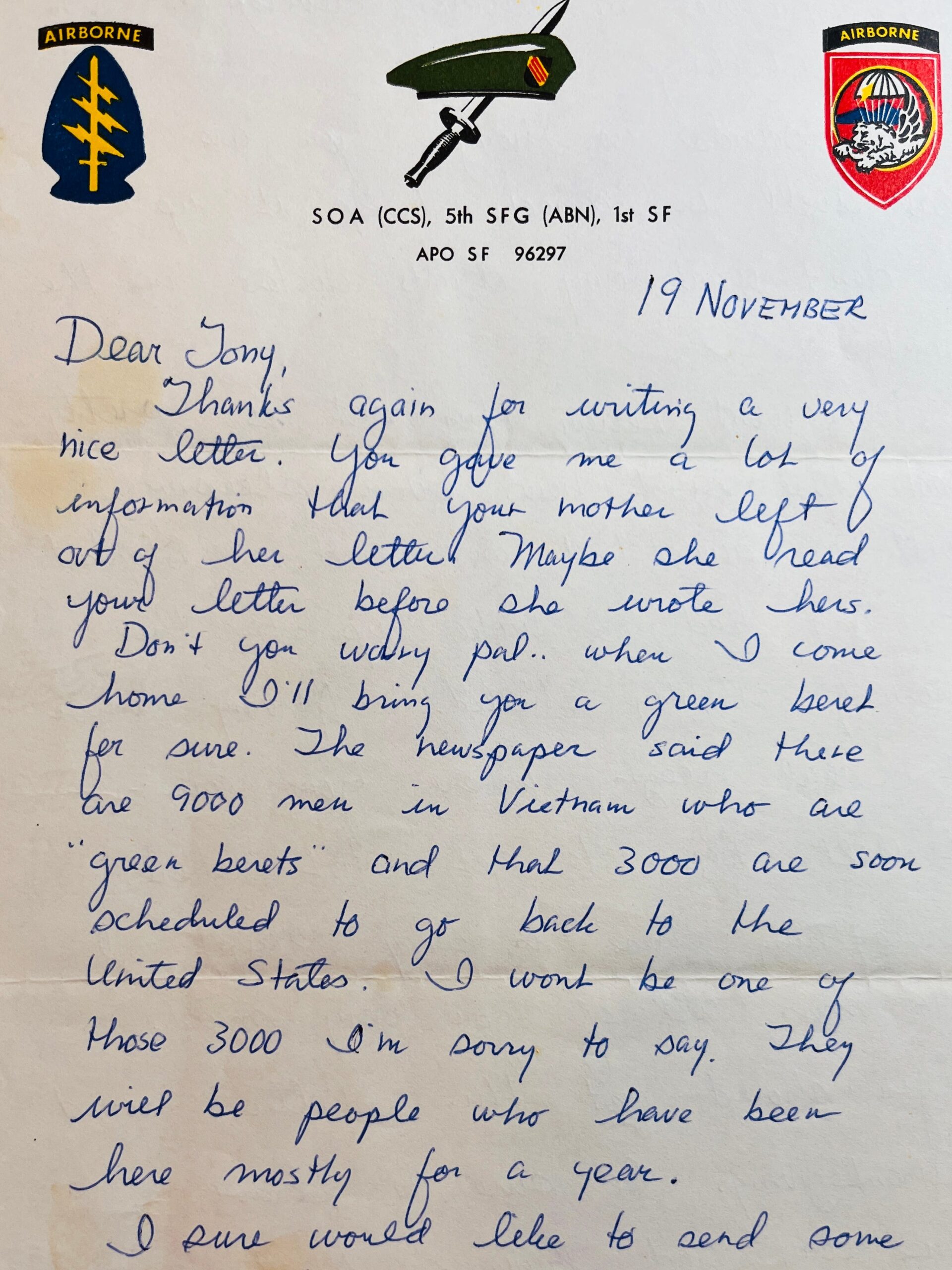

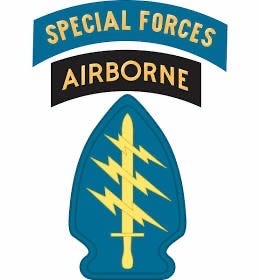

Distintivie Unit Patches, Flashes, and Badges of the Special Operations:

Military Assistance Command Vietnam–Studies & Observation Group (MACV-SOG)

The Vietnam War was America’s longest and most controversial conflict, and at its murky core lay a secret war few even knew existed. MACV-SOG — Military Assistance Command, Vietnam — Studies and Observations Group — was the elite unit that waged that secret war.

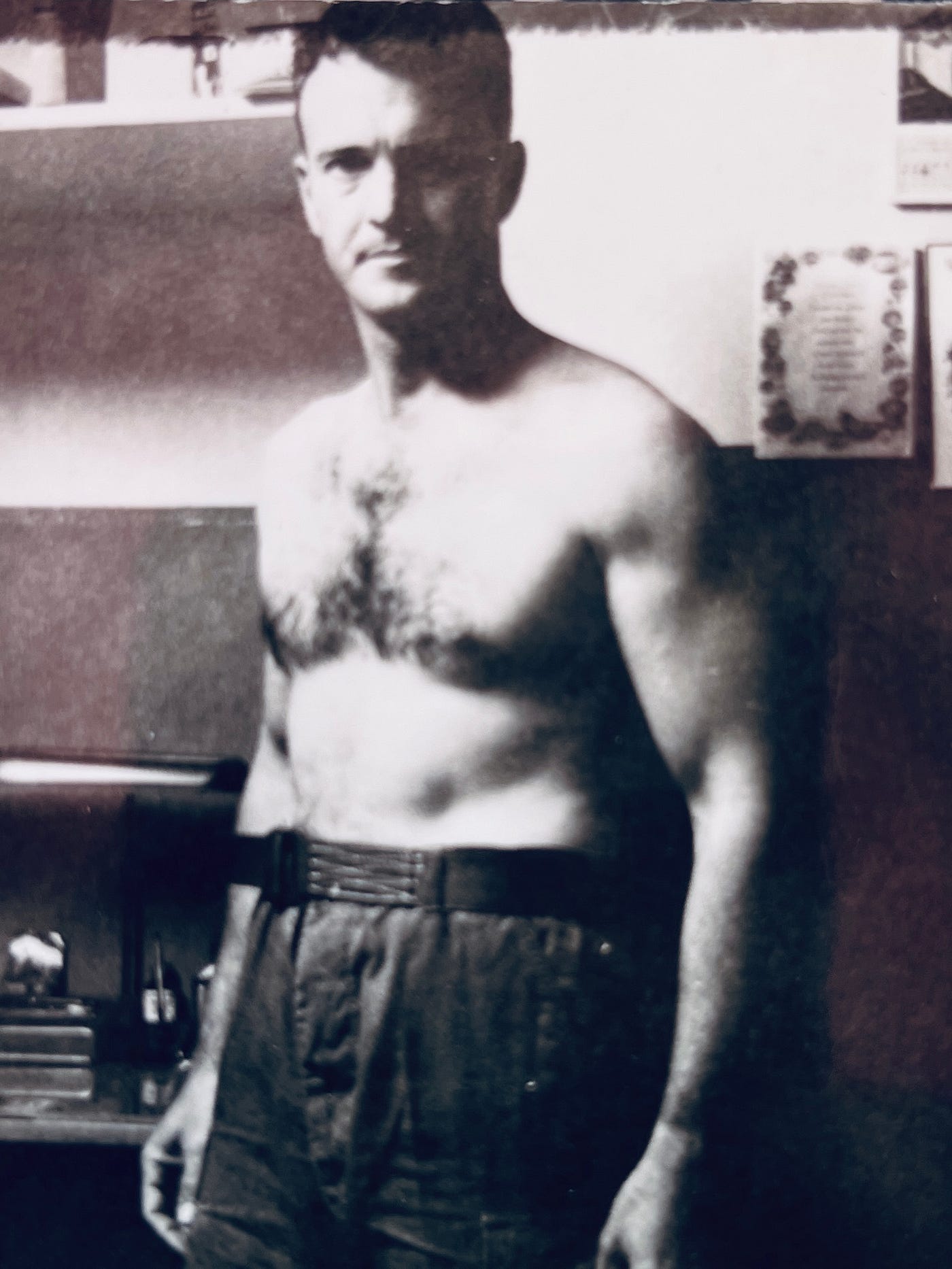

Established in 1964, it was composed of the best the U.S. military had to offer: Army Special Forces, Navy SEALs, Marine Recon, Air Force commandos, and CIA operatives. Their missions were so clandestine that, if captured, their government would deny any knowledge of them. These operatives conducted daring raids, reconnaissance, POW rescues, and psychological operations in Laos, Cambodia, and North Vietnam — places where we weren’t even supposed to be. My father was one of them.

Command & Control South (CCS) in Ban Mê Thuôt

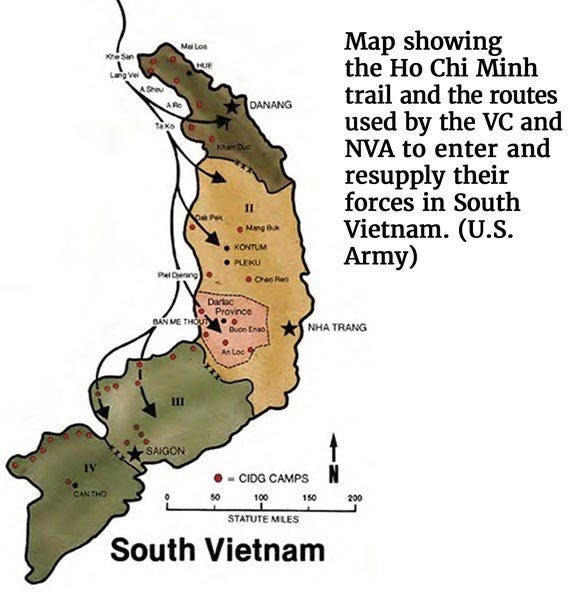

Assigned to Command & Control South (CCS), the smallest and perhaps most dangerous of SOG’s field units, my father served as its Deputy Commander. CCS was based out of Ban Mê Thuôt and operated in the dense jungles of southern Cambodia. Recon teams, Hatchet forces, and SLAM companies under CCS conducted missions across invisible lines drawn in Washington but ignored by enemy troops. The Ho Chi Minh Trail was their target — a jungle superhighway of men, weapons, and supplies. And my father helped direct the effort to stop it.

Ho Chi Minh Trail

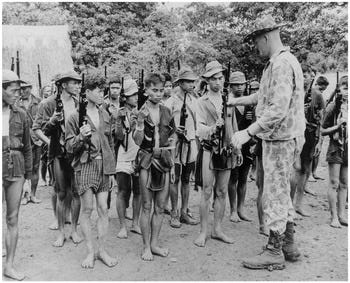

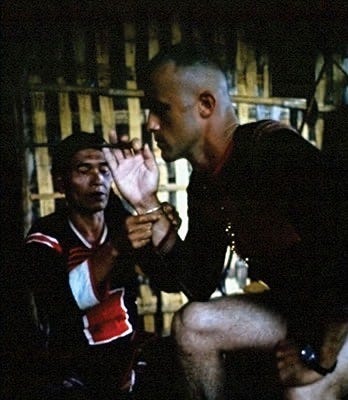

The Montagnard Tribes

The Montagnard people of Vietnam’s Central Highlands were among the fiercest and most loyal allies of MACV-SOG. These indigenous tribesmen, renowned for their jungle skills and unwavering courage, formed the backbone of many recon teams sent into Laos and Cambodia. On nearly every SOG mission, it was the Montagnards who shouldered the greatest burden — and suffered the greatest losses. They were often massacred by the dozen while shielding their American teammates. Yet their loyalty never wavered.

Before battle, a Montagnard shaman would sometimes perform a sacred two-hour ritual to drive out evil spirits, sealing the warrior bond with a simple yet powerful gesture: placing a hand-forged copper or brass bracelet on the wrist of the Green Beret. That bracelet symbolized trust, brotherhood, and a vow to protect. My father wore his Montagnard bracelet for years after the war, a silent tribute to those who fought — and died — beside him.

Parting Gift from the Officers & Men of MACV-SOG CCS 5th SF (Airborne)

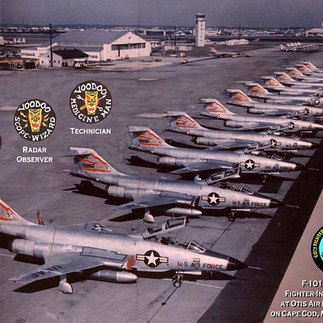

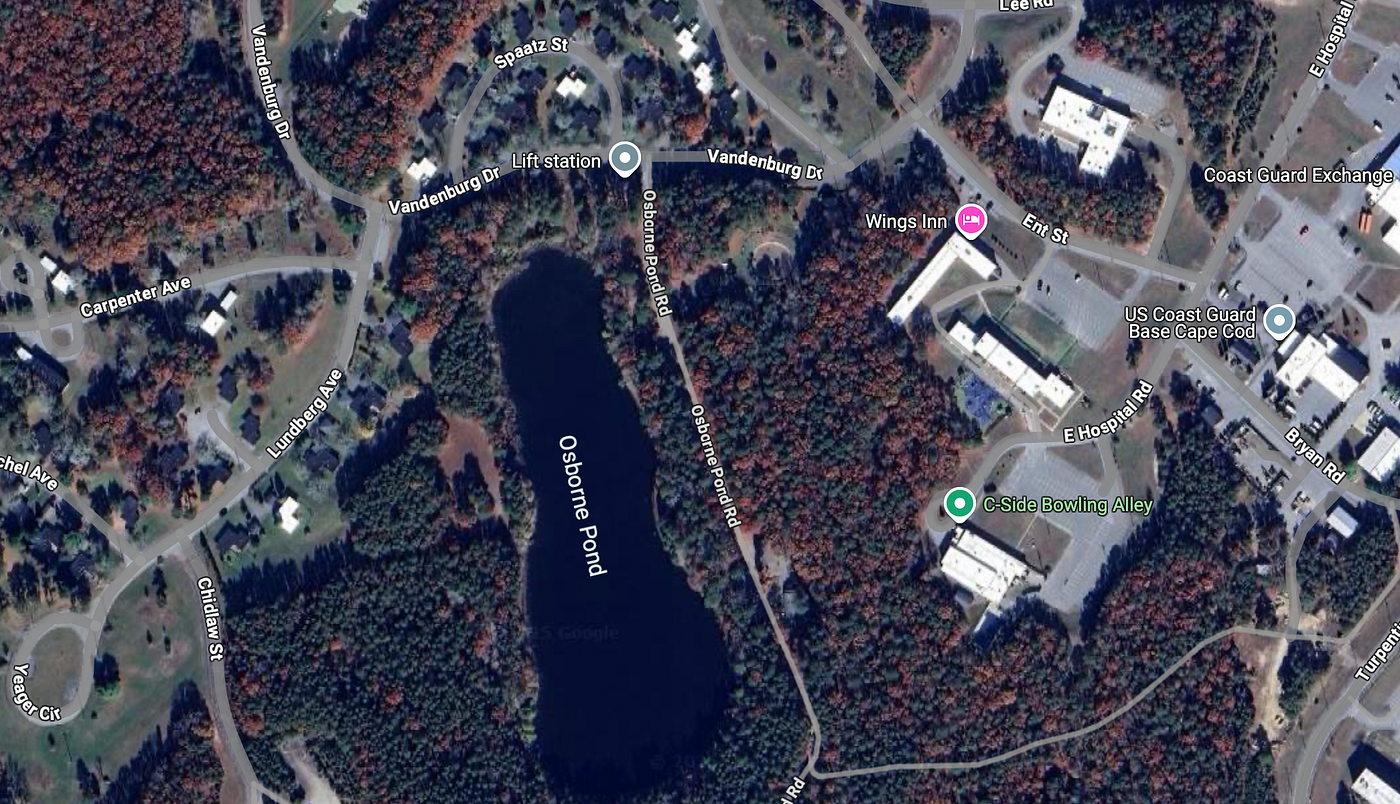

We Lived at Otis AFB, Cape Cod, While Dad Was At War

Unlike most American troops whose tours in Vietnam lasted twelve months, my father volunteered for an eighteen-month tour with MACV-SOG. It was dangerous, grueling, and top secret. While he lived in constant peril, commanding missions into the jungle with a rifle on his back, my mother and our family were stationed at Otis Air Force Base on peaceful Cape Cod. It was a stark contrast — he fought for his life daily while we played under blue skies on the lush grounds of one of New England’s most tranquil military bases.

My father arranged for us to live at 5356 Spaatz Street, Otis AFB, Massachusetts — just under two hours from our grandparents in Medford.

We saw my mother's family in the Boston area often, and they visited us just as frequently. We lived across the street from another Army family — the Napolis — and their son Joe Jr. became my closest friend, and we did everything together.

First Class Support at Otis Air Force Base

Somehow, my father had left such an impression with the base leadership that the Air Force took remarkable care of us. Military police visited regularly to check in. We were treated with kindness and respect, like we mattered. Directly across the street lived USCG Commander Ferguson, a Coast Guard pilot who flew rescue helicopters and had two daughters and a trained military police dog.

Commander Ferguson took Joe Napoli and me under his wing — he brought us to Little League, karate, and Boy Scouts. For the first time, I started to really thrive in Scouts. I even attended summer camp at Camp Greenough on Nantucket Island with Joe. Commander Ferguson became a kind of surrogate father while my real dad was away. His influence planted the seed that would later grow into my desire to become a military Flight Surgeon.

Most of our life at Otis was simple, safe, and full of joy. Blueberry picking became such a regular activity that I developed a lifelong dislike for blueberries. Our extended family stayed with us as often as they could. Our house was always filled with warmth, laughter, and love.

Tragedy Strikes the Elementary School

But not everything was light and carefree. I don’t remember much about sixth grade, but one winter morning is seared into my memory. My friends and I were walking to school, and they decided to take a shortcut across the frozen Osborne Pond. I hesitated. Something didn’t feel right. They laughed and called me a chicken as they stepped onto the ice. I chose to walk around the pond.

Moments later, I heard cracking. Then screams. The ice gave way, and the boys plunged into the freezing water. I ran to the school and got our sixth-grade teacher. He sprinted back with me, then dove into the icy water without hesitation. I watched as he broke the ice with his bare hands and head, trying to reach the boys. Four of my classmates died that day. Class was canceled. I never went near that pond again. To this day, I won’t stand on a frozen pond or lake.

Commander Ferguson began flying his helicopter over Osborne Pond each morning, smashing the ice to make sure no child would ever take that shortcut again.

Vietnam War on Television

And while we experienced joy and tragedy on Cape Cod, my father was thousands of miles away, walking the line between life and death every day. Though I was only in sixth grade, I was old enough to understand what was going on. Every night, I watched the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite, who updated America on the war my father was fighting. I didn’t know the details of his mission, but I knew it was something different — something dangerous.

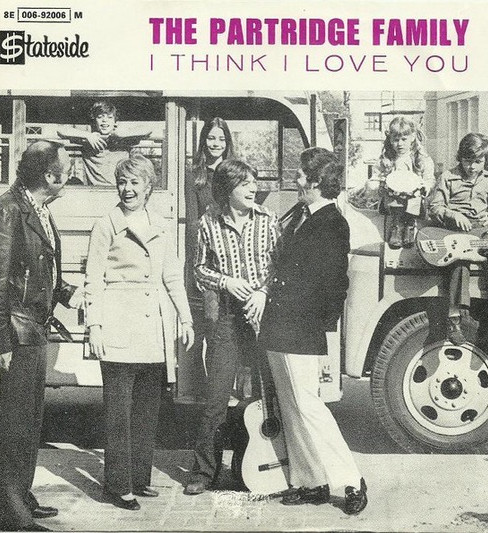

Music of 1970-1971

While my father was deep in the jungles of Vietnam in 1970 and 1971, the music playing back home felt like a snapshot of a world in flux. The Billboard Top 10 captured that contrast—The Partridge Family’s sugary “I Think I Love You” hit #1, while Edwin Starr’s explosive protest anthem “War” followed at #2.

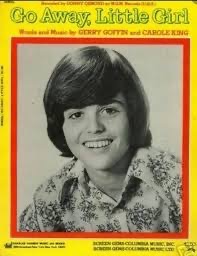

I remember my cousin Johnny Antonelli Jr. visiting us at Otis AFB in early ’71. His arms full of 45s—Neil Diamond’s aching “I Am… I Said,” Rod Stewart’s raspy 'Maggie May,' Isaac Hayes’ gritty 'Theme From Shaft.” My sister Diana swooned over Donny Osmond’s “Go Away Little Girl” and “One Bad Apple,” while I was absorbing everything from the Beatles’ “Let It Be” to the 5 Man Electrical Band’s rebellious “Signs” and Tommy James and the Shondells psychedelic “Crimson & Clover.” It was a strange, electric time—and the music captured every confusing, clashing note of it.

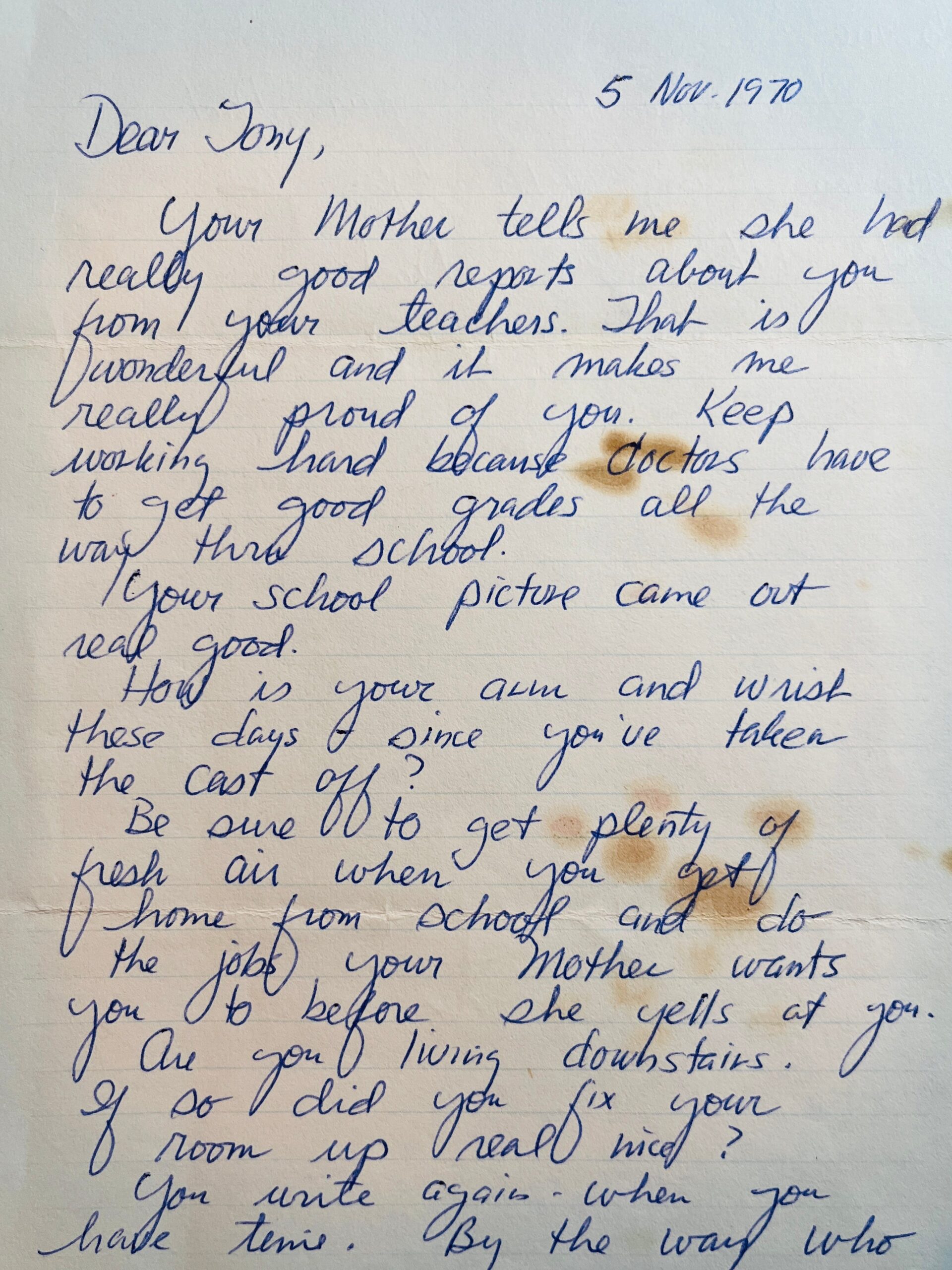

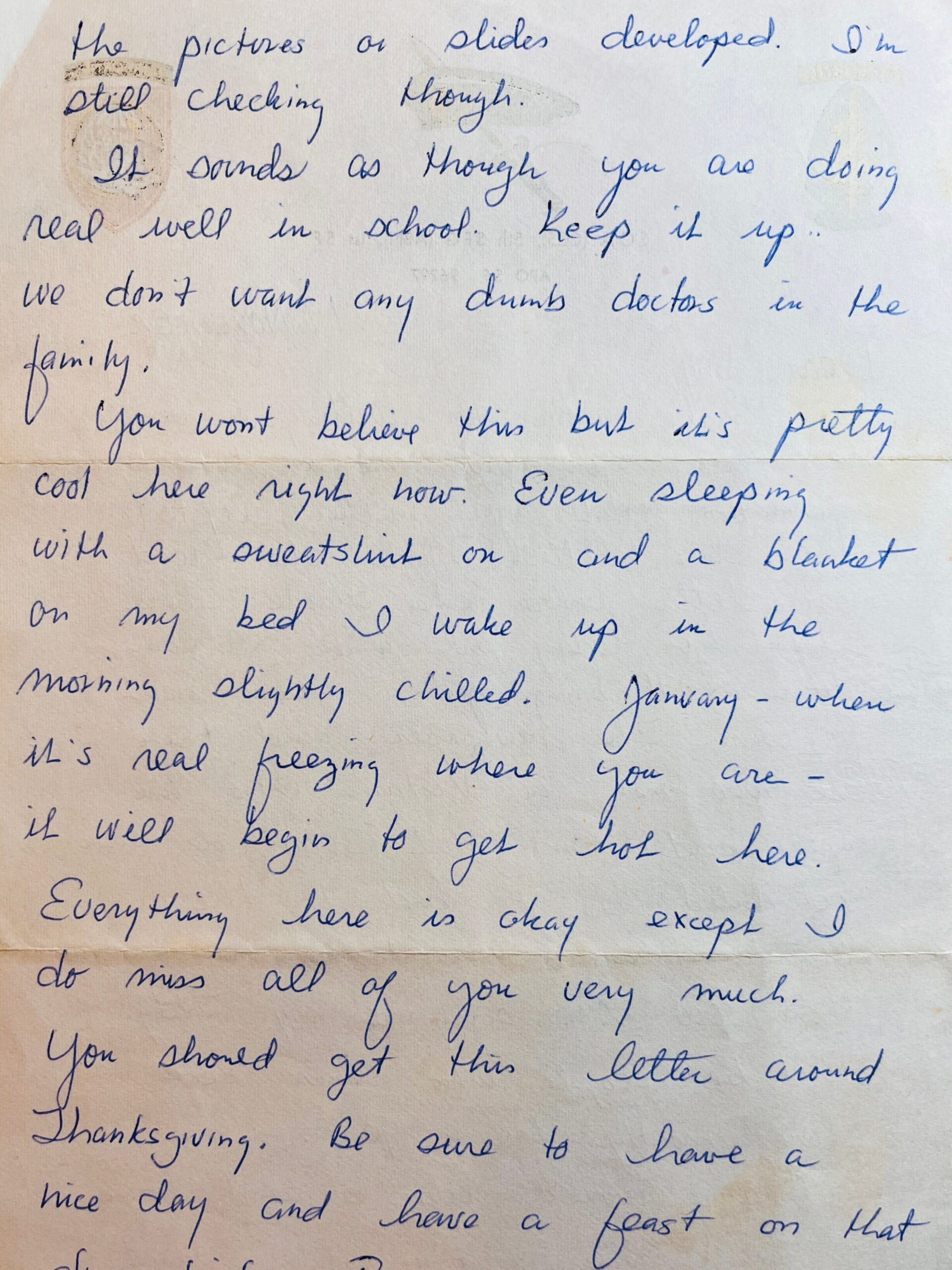

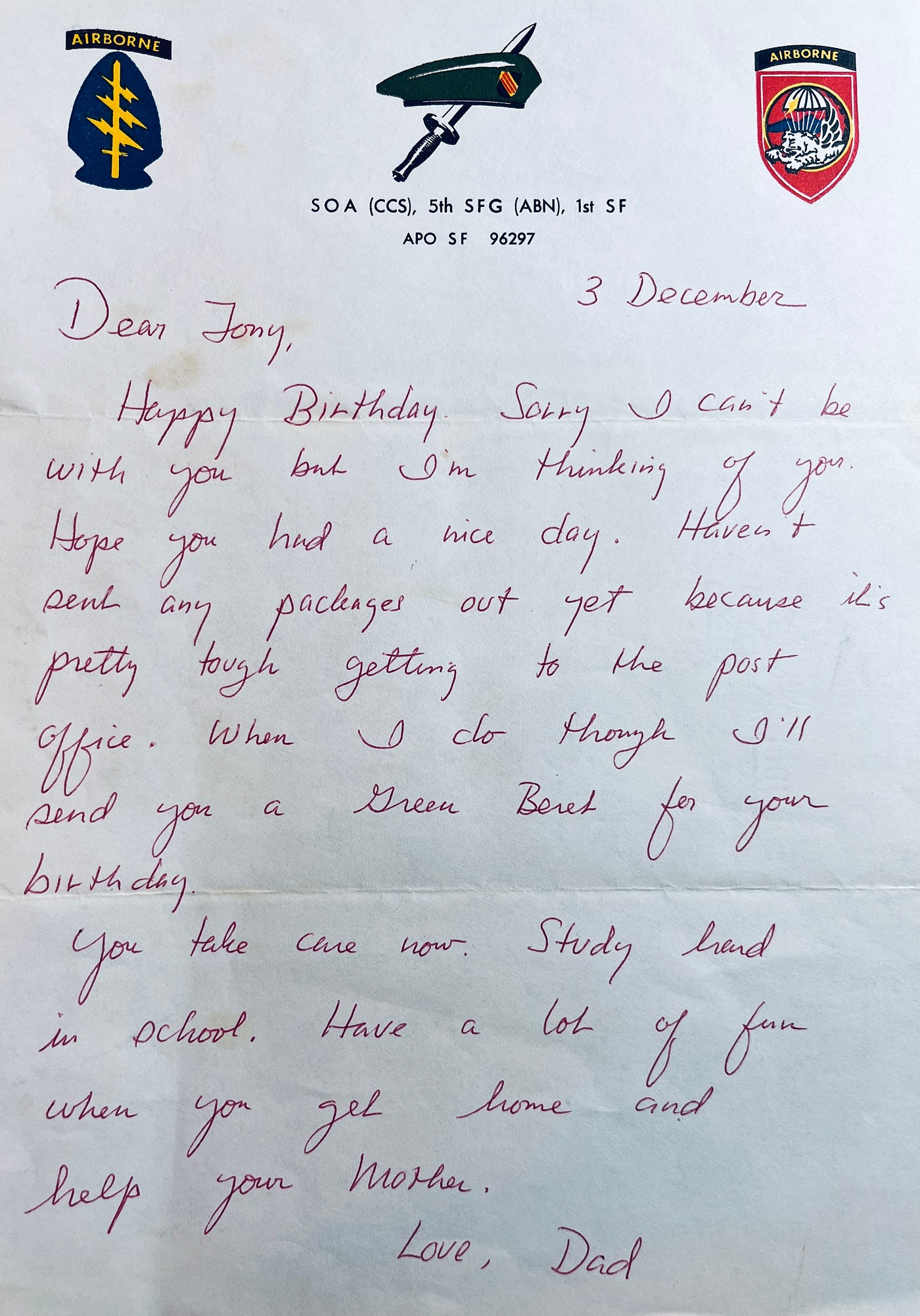

My Father’s Letters From Vietnam

My father wrote me often, sending handwritten letters filled with simple life messages and often with drawings he made of Viet Cong underground fortresses— little snapshots of life from halfway around the world.

Cassette Tape Messages From Vietnam

And he continued to send us cassette tapes, his calm voice crackling through the speaker as he described his days. I remember one message clearly: “Hey, kids. Hope you’re being good to your mom. I had a quick trip back to Saigon last week… Tell Mrs. Napoli I saw Joe — he’s doing fine, probably buying up half of Saigon!” Then suddenly, in the background — dogs barking. Explosions. Sirens. Machine gun fire. “Whoops! Gotta go!” The tape cut off. When he returned minutes — or days — later, his voice was just as casual: “Now, where was I? Oh, right. Joe looks good. I also saw Bob Moscatelli. I love and miss all of you. Oh, and I sent some new photos. Kids, be good to your mother. Edda, I love you with all my heart.”

Those tapes were more than updates — they were lifelines. We played them again and again. They made us feel close. They also gave me nightmares. In the photos he sent, I studied the barbed wire behind him, the machine gun nests, the rifles on the wall. It wasn’t abstract — it was real. And it was terrifying.

Rest & Recooperation (R&R) in Waikiki, Hawaii

Like all soldiers, my father received a short R&R during his deployment and spent it with my mother at the Hale Koa Hotel in Waikiki, Hawaii. I know they cherished that time, but I remember fewer photographs than from his earlier tour. Maybe that’s because this tour wasn’t just different. It was darker.

R&R Stateside

Because of the length of his deployment, he was also granted something almost unheard of — a one-week trip home to the States. My mother planned a massive party at Otis. All the relatives came to Cape Cod. There was food, laughter, a sense of celebration. But I noticed something no one else seemed to. My father spent most of that party with his back pressed against a building, barely moving. He wasn’t himself. I told myself he was jet-lagged. But years later, I realized the truth: just days earlier, he had been hiding in the jungle, possibly fighting hand-to-hand with enemy soldiers. Now he was expected to make small talk over potato salad. Of course, he was on edge.

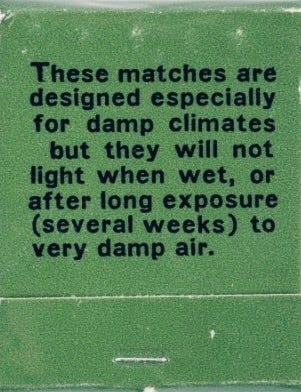

The moment I’ll never forget came when we took him to the airport. As he prepared to return to Vietnam, I saw something I’d never seen before: my father was nervous. Visibly so. He pulled a matchbook from his pocket, opened it, and began to read goodbye notes written on the cardboard striker. Then, quietly, he began to cry. My father — the Green Beret — was crying. In that moment, I knew: Vietnam was not just dangerous. It was hell. And he was walking straight back into it.

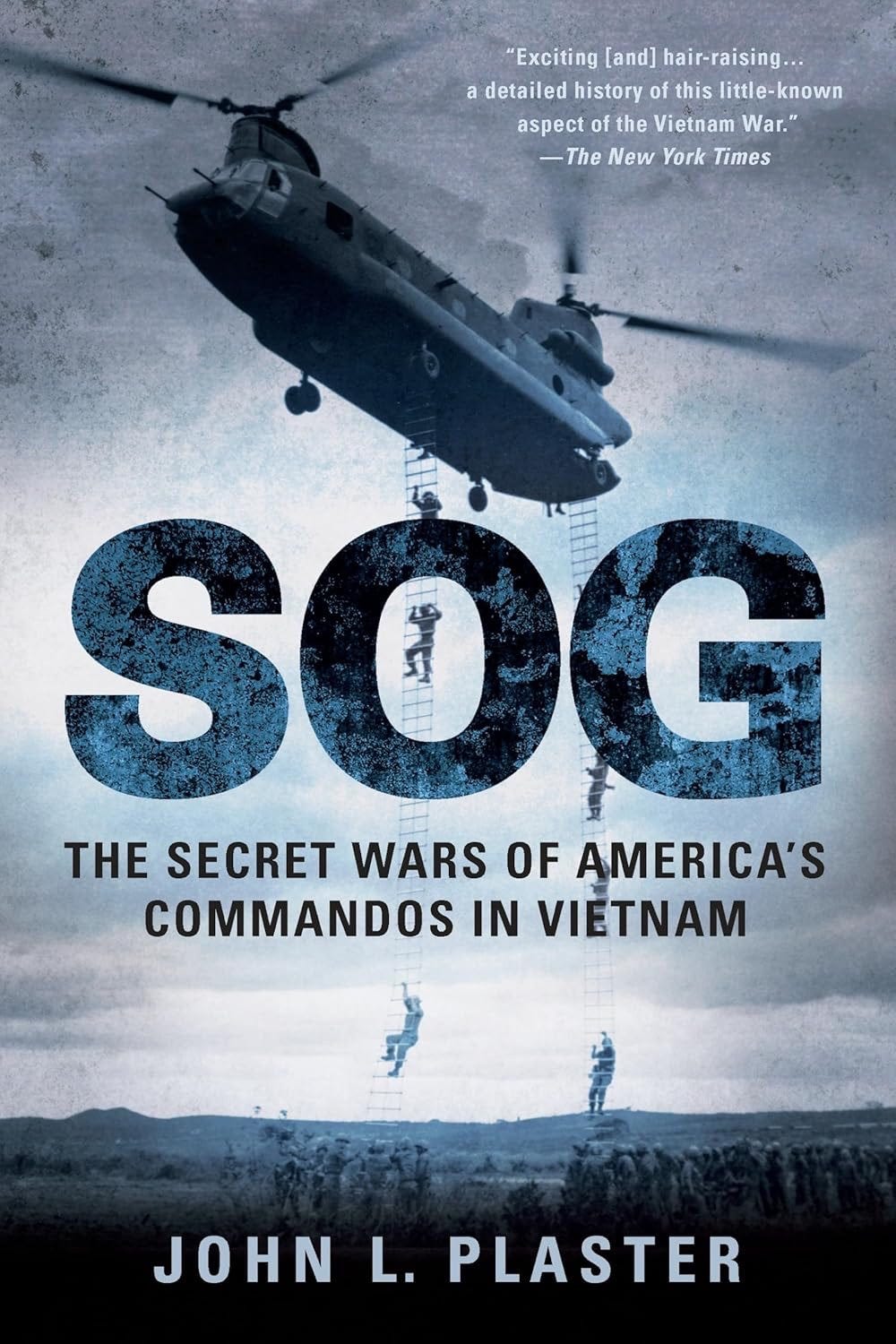

The Secret Wars of SOG and its High Cost of Life

Years later, I read SOG: The Secret Wars of America’s Commandos in Vietnam by Major John L. Plaster. It told of the kinds of missions my father directed — Top Secret patrols into Cambodia, ambushes, pilot rescues, and cross-border raids. These missions had a staggering 100% casualty rate. Montagnards were slaughtered. American Green Berets would cover each other’s escape with machine gun fire, often dying in the process.

And then I understood. I understood my father’s survivors’ guilt. I understood his silence. He wasn’t a Rambo., he didn’t talk about the war, he didn’t wear shirts or pins or bumper stickers. He simply came home and tried to live.

The Rare War Stories

He once told a story in private, during a quiet evening with an old MACV-SOG buddy he had invited over to meet me. I was just newly commissioned into the Army as a Chemical Corps officer and I my father invited his SOG friend who was also a chemical officer over to talk to me. They spoke in low voices, laughing softly. I sat nearby, listening.

The Reason for the Porsche 911

He described a mission — a parachute jump into Laos, deep into enemy territory. He landed in a rice paddy, rolled up his chute, and lay in the water, waiting for the extraction birds to clear the area. Then he saw a Viet Cong soldier with an AK-47 walking straight toward him. He whispered to himself: “F***. I’m dead. He has to see me.” He begged God for survival and made a silent promise: “If I make it out of this alive, I’ll throw out every stitch of clothing I own and buy a Porsche 911.” The soldier turned and walked away. My father eventually made it home safely. When we moved to Germany for a third time, He tossed out all his clothes — much to my mother’s horror — and filled his closet with tacky 1970s leisure suits. Then he bought his Porsche 911.

Don’t Worry–They Won’t Get Away!

He never wore his story — but I carry it for him now. For years, his Green Beret sat quietly in a drawer, beside a well-worn Special Forces manual and a captured Viet Cong flag — silent relics of a war he rarely spoke about. But it was the plaque given to him by the officers and men of MACV-SOG Command & Control South that told me everything I needed to know.

Engraved on a placque using my father’s own commanding words in the heat of battle as they cried out to him: Sir, “THEY GOT US SURROUNDED” — and his legendary reply — “DON’T WORRY, THEY WON’T GET AWAY!” — it captured the unshakable courage and fierce resolve that defined his leadership. It’s not easy growing up in the shadow of a Green Beret hero. But when that shadow is cast by a man like my father, you don’t run from it. You stand in it with pride, hoping one day to be worthy of its strength.

MACV-SOG Mementos That My Father Gave Me

“THEY GOT US SURROUNDED. DON’T WORRY, THEY WON’T GET AWAY!”

It’s not easy growing up in the shadow of a Green Beret hero — but I wouldn’t trade that shadow for anything in the world.

A few more letters from my father in Ban Mê Thuôt, Vietnam